|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Protestantism

|

|

Dr.

Marguerite Connor

|

| |

| In the 16th

century, alarmed at the corruption of the Catholic Church, a

number of priests tried to get Christianity back to its earlier

simplicity and biblical basis. At first, they tried for

reform, but they soon believed that only a total split from the Church

would do. These events revolve around four major reform

movements: the Lutherans, Anglicans, Anabaptists, and the Reformed

Tradition. Chief names among these protesters (or

"Protestants") were Martin Luther, Ulrich (or Huldreich) Zwingli,

John Calvin and John Knox.

There are many, many

branches of Protestantism, with different beliefs in the various

streams. Here, I will introduce the four movements and men above to

point to the different paths.

More and more doctrinal

differences became apparent and the relatively unified Christianity

split into a number of warring factions. Thousands were killed through

the 16th and 17th centuries in the name of the

Christian religion.

Today, in the spirit of

ecumenism, Catholics and Protestants are "brothers in Christ."

Except in rare cases, the hatred is gone.

|

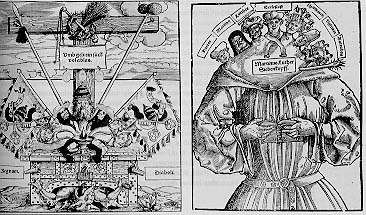

| Around 1530 a

Lutheran cartoon was circulated in Germany which turned the

papacy into the "seven-headed beast" of the Book of

Revelation. The papacy''s "seven heads" consist of pope,

cardinals, bishops, and priests; the sign on the cross reads "for

money, a sack full of indulgences"; and a devil is seen emerging from

an indulgence chest below. |

Left: The Seven-Headed Papal Beast.

Right: The Seven Headed Martin Luther.

|

In response, a

German Catholic propagandist showed Luther as Revelation''s

"beast." In the Catholic conception Luther''s seven

heads show him by turn to be a hypocrite, a fanatic, and

"Barabbas"--the thief who should have been crucified instead of Jesus. (Lerner 459) |

|

Martin Luther: Theological premises

/ Anglicanism / History and Politics Martin Luther: Theological premises

/ Anglicanism / History and Politics

Ulrich Zwingli: Anabaptist / Reformed Churches Ulrich Zwingli: Anabaptist / Reformed Churches

John Calvin: Breaks with Lutheran Beliefs John Calvin: Breaks with Lutheran Beliefs

John Knox John Knox

|

| |

Martin Luther: Theological Premises /

Anglicanism / History and Politics Martin Luther: Theological Premises /

Anglicanism / History and Politics |

|

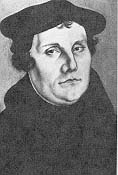

German

reformer and founder of the Lutheran church

Martin Luther. A portrait by

Lucas Carnach. (Lerner 452)

Luther is the most famous of all

the reformers, for he is credited with initiating the Protestant

reformation on October 31, 1517 when he nailed his now famous "95

Theses" objecting to the Catholic indulgence doctrine to the

door of a church in Wittenberg, Germany.

Martin Luther was originally a

Roman Catholic monk and scholar who soon found himself objecting not

only to the abuses in his Church, but more crucially, to some of its

doctrines, or teachings. After the publication of his "95 Theses,"

Luther found himself in more and more trouble with Church authorities

so that by 1519 he finally broke with the Church and went on to write

and preach and through these activities, continue the work of the

Reformation.

|

| |

| |

Theological

premises

Luther finally came up with three

main premises, which are also accepted by many other Protestant groups.

Christians should believe in:

- Justification by faith (it is

through faith only that Christians will be saved, not by Good Works as

the Catholic Church maintained)

- The primacy of Scripture (the

literal meaning of the Bible should be preferred to any traditional or

learned readings, and anything not specifically grounded in Scripture

was to be rejected)

- The "priest-hood of all

believers" (ordained priests were not the only ones who should be

considered members of the "true spiritual estate," so here Luther did

away with the priesthood, though many Protestant groups still use

ministers or pastors to lead others)

Luther also explained the sacrament

of the Eucharist in terms of consubstantiation. This is the conviction

that Christ is truly present in the celebration of the Eucharist. This

doctrine comes from the same Aristotelian philosophical assumptions as

the doctrine of transubstantiation, but while believers in

transubstantiation believe that during the celebration of the Eucharist

the bread and wine literally change to the body and blood of Jesus,

believers in consubstantiation believe that the bread and wine remain

bread and wine which also includes Christ''s presence.

Lutheranism was formed out of the

works of Luther. His Small Catechism, written in 1529, is a basic

statement of faith for all Lutherans. One of Luther''s significant

contributions to all of Christianity is his emphasis on singing hymns

in worship, many of which he authored.

Many Germans followed Luther and

his teachings, but this particular form of Protestantism didn''t prove

very popular beyond its native Germany, though the majority of

Scandanavian Protestants are Lutheran. There are also large numbers of

Lutherans wherever Germans settled, especially in America and in some

part in Australia.

BACK

TOP

Anglicanism takes its historical root in an essentially

political battle between the papacy and the English King, Henry

VIII (1491-1547). Henry''s need for an heir and a divorce from

his wife, Catharine of Aragon, resulted in Henry declaring himself head

of the Church of England in1534 in direct defiance of the papacy.

Henry''s concerns were more

secular than theological. He was never truly "Protestant", holding on

to the essentials of Roman Catholicism. His efforts in church affairs

were clearly aimed at strengthening England''s position in the power

structure of Europe; consequently, the Episcopal Church, which is

Anglican, is in many ways much closer in theology, government and

practice to the Roman Church than to the Protestant Church with which

it is usually associated. But many of the theologians surrounding Henry

were sincere in their religious questioning and were followers of the

teachings of Luther.

BACK

TOP

History and

Politics

After Henry''s death, he was

followed on the throne by his young son, King Edward VI (son of the

Protestant Jane Seymour), a staunch Protestant influenced by the

teachings of Calvin, so the Church of England moved closer to its

continental cousins.

|

Edward"s early death at

the age of 16, after only seven years as king, left the throne to his

Catholic sister, Queen Mary I (daughter of Henry and

Catharine of Aragon). Known as "Bloody Mary,"

during her five-year reign, Mary attempted to bring England

back to the Roman Catholic Church. She martyred many

people in the process (hence the nickname), alienated the British and

ultimately failed.

Mary

Tudor (Lerner 467)

|

Her

Protestant sister, Queen Elizabeth I (daughter of the

Protestant Anne Boleyn) followed her on the throne. One of England''s

shrewdest rulers, Elizabeth realized that the "religious question"

needed to be settled in England once and for all. No religious zealot

herself (an unfortunate tendency shared by her brother and sister), by

"An Act of Supremacy" in 1559, Elizabeth prohibited the exercise of any

authority by foreign religious powers and made herself "Supreme

Governor" of the English Church, a more "Protestant" choice than

her father''s title of "Supreme Head," since Protestants see Jesus

Christ as the head of the church. Her

Protestant sister, Queen Elizabeth I (daughter of the

Protestant Anne Boleyn) followed her on the throne. One of England''s

shrewdest rulers, Elizabeth realized that the "religious question"

needed to be settled in England once and for all. No religious zealot

herself (an unfortunate tendency shared by her brother and sister), by

"An Act of Supremacy" in 1559, Elizabeth prohibited the exercise of any

authority by foreign religious powers and made herself "Supreme

Governor" of the English Church, a more "Protestant" choice than

her father''s title of "Supreme Head," since Protestants see Jesus

Christ as the head of the church.

She accepted the Protestant

ceremonial reforms made during the reign of her brother, but she

retained church government by bishops and left the definitions of some

controversial articles of faith, in particular the meaning of the

Eucharist, vague enough to satisfy the scruples of all but the most

extreme Catholics and Protestants.

As a result of these reforms, the

Anglican church today embraces diverse elements from the "high church"

Anglo-Catholics who only differ from Roman Catholics in rejecting papal

supremacy, to the "low church" Anglicans who are as Protestant in their

practices as other modern Protestant denominations.

BACK

TOP

|

| |

Ulrich Zwingli: Anabaptist / Reformed Churches Ulrich Zwingli: Anabaptist / Reformed Churches |

|

Leader

of the Reformation in Switzerland (Portrait Bainton 79)

At first a rather indifferent

Catholic priest, by 1516 Zwingli came to conclude that contemporary

Catholic theology and observances conflicted with the Bible. In 1522,

Zwingli began attacking the authority of the Church in Zurich, and soon

all of northern Switzerland was following his leadership. He helped

institute reforms that closely followed those of Martin Luther in

Germany.

He differed from Luther on the

meaning of the Eucharist. While Luther and his followers believed in

the real presence of Christ''s body, Zwinglianism believed that Christ

was present merely in spirit. Therefore, the sacrament conferred no

grace at all and was maintained merely as a memorial service. This

difference was enough to prevent Zwinglians and Lutherans from uniting.

This forced Zwingli and his followers to fight alone, and in a battle

with Catholic forces in 1531 Zwingli was killed.

His movement later became

absorbed by the more radical Protestantism of Calvin,

but first came the short-lived movement called Anabaptism.

|

| |

Anabaptist

This

term refers to a collection of the most radical groups within the

Protestant Reformation. The term literally means "re-baptizers"

a reference applied by their opponents because Anabaptists did not

believe in baptizing infants and so insisted on the re-baptism of all

believers. They also believed that one had to follow the guidance of

one''s own "inner light" in choosing church membership. Unfortunately

this apolitical nature in a time when religion and politics were

tightly intertwined made "official"‥ acceptance impossible. This

term refers to a collection of the most radical groups within the

Protestant Reformation. The term literally means "re-baptizers"

a reference applied by their opponents because Anabaptists did not

believe in baptizing infants and so insisted on the re-baptism of all

believers. They also believed that one had to follow the guidance of

one''s own "inner light" in choosing church membership. Unfortunately

this apolitical nature in a time when religion and politics were

tightly intertwined made "official"‥ acceptance impossible.

Anabaptist Martyrs (Picture Bainton 102)

There are four general categories

of Anabaptists: the main liners, those who formed communities to live a

strict biblical life; the spiritualists, those who appealed to the Holy

Spirit more than the Bible; the rationalists, those who read the Bible

in the light of reason and thus rejected many traditional beliefs; and

the revolutionaries, those who proposed bringing in the Kingdom of God

by the sword.

These groups were ruthlessly

persecuted, and except for the Mennonites, who are mainly found in

America today, they have few descendants.

BACK

TOP

Reformed

Tradition or Churches

These are the churches that

follow the policies or doctrines of the reformers Zwingli or Calvin

rather than the Lutheran tradition. One of the chief distinctions of

the reformed churches is their doctrine of the Eucharist. It rejects

both transubstantiation (Roman Catholic) and consubstantiation

(Lutheran)

The best known of the Reformed

Churches are the Presbyterian Church and the Dutch Reformed

Church.

BACK

TOP

|

| |

John Calvin: Breaks with Lutheran beliefs John Calvin: Breaks with Lutheran beliefs |

|

Trained

as a lawyer and theologian in France, Calvin was forced to leave Paris

in 1535 because of his indirect support of Martin Luther. After that

time, he centered his activity in Geneva where he served as a teacher,

pastor, and mayor of the city. His work, The Institutes of the

Christian Religion (1536) systematically presents a Protestant

response to Roman Catholic doctrine and formed the theological basis

for the Reformed tradition, and it is viewed as one of the great

classics of Christian history. It was also this book which thrust him

into the forefront of Protestantism. Trained

as a lawyer and theologian in France, Calvin was forced to leave Paris

in 1535 because of his indirect support of Martin Luther. After that

time, he centered his activity in Geneva where he served as a teacher,

pastor, and mayor of the city. His work, The Institutes of the

Christian Religion (1536) systematically presents a Protestant

response to Roman Catholic doctrine and formed the theological basis

for the Reformed tradition, and it is viewed as one of the great

classics of Christian history. It was also this book which thrust him

into the forefront of Protestantism.

Above

& Left: Calvin as Seen by His Friends and His Enemies.

(Lerner 474)

Above : An idealized

contemporary portrait of Calvin as a pensive scholar.

Left: A Catholic

caricature in which Calvin''s face is a composite made from fish, a

toad, and a chicken drumstick.

Many foreigners were drawn to

Geneva either for refuge or instruction, often returning home to become

fierce proponents of Calvinism. John Knox, who went to Geneva three

times to study with Calvin, called Calvin''s Geneva "the most perfect

school of Christ that ever was on earth since the days of the

Apostles."

|

| |

Calvin''s Theology

Since according to Calvin, the

Bible specified the nature of theology and of human institutions, in The

Institutes of the Christian Religion, he tried to explain

Bible theology by following the articles of the Apostles'' Creed.

Calvin explained that the entire

universe in dependant upon the will of God, who created all things for

His own greater glory. Because of the original fall from grace (Adam

and Eve''s eating of the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge as told in

Genesis), all human beings are sinners by nature, bound to an

inheritance they cannot escape.

Predestination

But out of His great mercy God

has predestined (already determined that) some humans will receive

eternal salvation in heaven while all other humans will be damned to

the torments of hell. Nothing humans can do will alter this fact. Their

fate is sealed.

This does not mean that

Christians can do anything they wish. If they are one of the elect, God

has also given them a predisposition to live correctly. Upright

behavior is a sign, though a sometimes imperfect one, of being one of

the elect.

Public professions of faith and

active participation in the sacrament of the Eucharist were also signs

of being one of the elect. But Calvin also required a life of piety and

morality.

TOP

Breaks with

Lutheran beliefs

While Calvin admitted a

theological debt to Luther, the two men differed on many important

points.

- Action - While Luther urged an

acceptance of the tribulations of this life, Calvin called Christians

to an active life in which the world was mastered in unending labor for

the greater glory of God.

- The Sabbath - Luther continued

in the traditional Sabbath observance of church services, but otherwise

was not overly strict. Calvin reinstituted the Jewish ideas of

the Sabbath by calling for strict taboos against anything faintly

resembling worldliness.

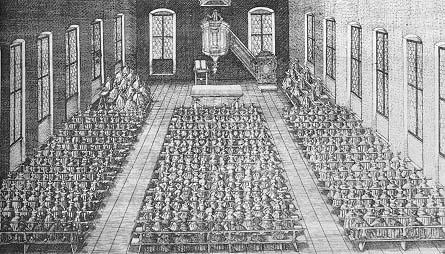

- Church government and ritual -

Luther broke with the Catholic hierarchy, but Lutheran district

superintendents resembled Catholic bishops in many ways, and Luther

retained many forms of Catholic ritual such as vestments (special

clothes for the clergy during ceremonies) and altars in church. Calvin

forcefully rejected anything that had hints of "popery."‥ He argued for

the elimination of all hierarchy, allowing churches to be governed by

elected ministers (presbyters) and assemblies of ministers. He also

called for simplicity in church ceremonies and prohibited all ritual,

vestments, instrumental music, images and stained glass windows.

Services

in a Calvinist Church (Lerner 473)

Services

in a Calvinist Church (Lerner 473)

Large followings

Calvin attracted large numbers of

followers. Soon Calvinists became the majority in Scotland, where they

were known as Presbyterians; a majority in Holland, where they founded

the Dutch Reformed Church; a substantial minority in France, where they

were known as Huguenots; and a substantial majority in England, where

they were called Puritans.

BACK

TOP

|

| |

|

|

John Knox John Knox |

|

Ordained a priest in

the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland around 1530, Knox had already

begun to question the scholastic teachings of his day. When his close

friend George Wiseheart, a young man with Protestant leanings, was

burned at the stake by a Catholic Cardinal for his part in trying to

marry the Catholic Mary Queen of Scots to the young Protestant English

Prince Edward (son of Henry VIII), Knox became the enemy of the Roman

Catholic Church.

He remained a preacher, though, in

the mold of Calvin, and as such, accused the Catholic clergy of

Scotland of being "gluttons, wantons and licentious revelers, but who

yet regularly and meekly partook of the sacrament [the Eucharist]."

He traveled to Geneva three times

to study under Calvin who had a high regard for the Scotsman. Knox

returned to Scotland, married at age 38, and was widowed a few years

afterward.

His book, The First

Blast of the Trumpet Against the Monstrous Regiment of Women,

had Mary Tudor (the Catholic queen of England) and the Catholic Mary

Queen of Scots, in mind. It was Knox who would lead the movement forcing

the abdication of the Roman Catholic monarch, Mary, Queen of Scotland,

in 1567.

TOP

|

| |

Rise

of Protestantism Rise

of Protestantism

|

| |

Below

is a chart that shows how the groups grew in historical order.

Pre-Reformation Period

Roman Catholics

Gnostics c. 200

Coptic Church 425

Eastern Orthodoxy 1054

Waldensians 1173

-- Peter

Waldo

Lollards c. 1379

-- John

Wycliffe

Hussites 1415

Sixteenth

Century

Lutheranism 1517

-- Martin

Luther

Anabaptism 1521

Scandinavian Lutherans

Christian II

Zwinglianism 1523

-- Huldreich

Zwingli

Anglicanism 1534

-- Henry

VIII/Bishop Cranmer

Mennonites c. 1536

-- Menno

Simons

Calvinism 1536

-- John

Calvin

German Reformed Church c. 1540s

Hungarian Reformed Church c. 1550s

French Calvinists (Huguenots)

Scottish Presbyterians c. 1560

-- John Knox

Congregationalism (Puritans)

Dutch Reformed Church c. 1570s

Seventeenth

Century

English Baptists c. 1606

-- John Smyth

Quakers 1647

-- George Fox

Amish c. 1690

-- Jacob

Ammon

|

Eighteenth Century

Moravians c. 1722

-- Count

Nikolaus von Zinzendorf

Methodism 1739

-- John

Wesley

Shakers 1776

-- Ann Lee

Protestant Episcopal Church 1785

Swedenborgians 1789

-- Emanuel

Swedenborg

Nineteenth Century

United Brethren in Christ

1800

-- Philip

Otterbein

Evangelical Association 1807

-- Jacob

Albright

Unitarianism USA 1819

-- William

Ellery Channing

Christian Churches 1827

-- Barton V.

Stone

Disciples of Christ 1831

-- Thomas

Campbell

Anglo-Catholicism 1833

Seventh Day Adventists 1863

Salvation Army 1865

-- William

Booth

Christian Science 1879

-- Mary

Baker Eddy

|

TOP

|

| |

|

Church

Affiliations Flow Chart-- to show how

they grew theologically Church

Affiliations Flow Chart-- to show how

they grew theologically

|

| |

| LUTHERANS

Lutheranism 1517

-- Martin

Luther

Scandinavian Lutherans

-- Christian II

ANABAPTISTS

Anabaptism 1521

Mennonites c. 1536

-- Menno Simons

Quakers 1647

-- George Fox

Amish c. 1690

-- Jacob Ammon

Shakers 1776

-- Ann Lee

|

ANGLICANS

Anglicanism 1534

-- Henry VIII/Bishop Cranmer

Methodism 1739

-- John Wesley

Protestant Episcopal Church 1785

Anglo-Catholicism 1833

|

REFORMED/

CALVINISTS

Zwinglianism 1523

-- Huldreich Zwingli

Calvinism 1536

-- John Calvin

German Reformed Church c.

1540s

Hungarian Reformed Church

c. 1550s

French Calvinists

(Huguenots)

Scottish Presbyterians c.

1560

-- John Knox

Congregationalism (Puritans)

Dutch Reformed Church c.

1570s

|

OTHERS

English Baptists c. 1606

-- John Smyth

Moravians c. 1722

-- Count

Nikolaus von Zinzendorf

Swedenborgians 1789

-- Emanuel

Swedenborg

United Brethren in Christ

1800

-- Philip

Otterbein

Evangelical Association 1807

-- Jacob

Albright

Unitarianism USA 1819

-- William

Channing

Christian Churches 1827

-- Barton V.

Stone

Disciples of Christ 1831

-- Thomas

Campbell

Seventh Day Adventists 1863

Salvation Army 1865

-- William

Booth

Christian Science 1879

-- Mary Baker

Eddy

|

TOP

|

| |

|

Picture Sources:

1. Lerner, Robert E. et al. Western

Civilizations: Their History and Their Culture. 12th

Ed. New York: Norton, 1993.

2. Bainton, Roland H. The

Reformation of the Sixteenth Century. Boston: The Beacon P,

1952.

3. Ferguson, Margaret W. et al.

eds. Rewriting the Renaissance: The Discourses of Sexual

Difference in Early Modern Europe. Chicago: U of Chicago P,

1986. |

|

|

|

|