|

|

|

|

| Elizabeth Bishop |

| �̲���աE�ѨF�� |

| �D�n�����GPoem |

| ��ƴ��Ѫ̡GKate Liu/�B����;Ray Schulte/���ùp |

|

|

|

References

|

| |

|

Elizabeth Bishop's Paintings Elizabeth Bishop's Paintings

Bishop and Brazil Bishop and Brazil

Bishop and Psychobiography Bishop and Psychobiography

|

| |

| |

|

Elizabeth

Bishop's Paintings Elizabeth

Bishop's Paintings

|

| |

Merida

from the Roof

Merida

from the Roof

This view of

Merida is the jacket illustration for The Complete Poems:

1927-1979. ("The branches of the date-palms look

like files.") (Benton,

26-27)

Lamp

Lamp

The

inscription reads: For

Lota: /Longer than Alladin's burns, /Love, & many Happy Returns

/March 16th, 1952 / Elizabeth.

From a prominent Brazilian family, Lota (Maria Carlota Costellat de

Macedo Soares) was Bishop's lover from 1952 until her suicide in

1967, This painting, with its implication of wishes granted

and darkness banished (and its pun on "touching"), dates from their

first year together. (Benton, 60-61)

|

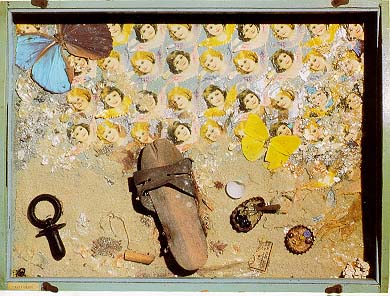

Anjinhos Anjinhos

--Anjinhos

(angels) was inspired by the drowning of a young girl in Rio de

Janeiro. Both it and, to a lesser extent, Feather

Box recall the work of Joseph Cornell--his "Monuments to

every moment," as Bishop translates the phrase, in her version of

Octavio Paz's poem "Objects & Apparitions." (Benton,

50-51)

|

Red

Stove and Flowers

Red

Stove and Flowers

The inscription

reads: May the Future's

Happy Hours /Bring you Beans & Rice & Flowers / April

27th, 1955 / Elizabeth.

This is

one of the very few pictures

composed as an explicit symbolic statement. It contains a

poem--and a formula of proportion--for domestic balance. The

stove is "magic"; and against a wall of blackness, the aggregate white

voices an impassioned reassurance. All underlined by one of

her specialties: wood grain. (Benton,

66-67)

|

from Benton, William, ed with an

introd. Elizabeth Bishop: Paintings.

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1966.

TOP

|

| |

Bishop

and Brazil Bishop

and Brazil |

| |

| From a visitor to a resident of

Brazil, Bishop's affection toward it's land and people is expressed

through her art, writing and painting. Here are a Bishop's painting of

Brazilian landscape and some photos of Casa Mariana, the house Bishop

lived in Ouro Preto, Brazil and is named in honor of Marianne Moore, an

influedntial poet friend of Bishop. |

| "Brazilian

Landscape" from EXCHANGING HATS: PAINTINGS by

Elizabeth Bishop.

Copyright?1996 by Alice Helen

Methfessel. Reproduced by permission ofInc. Farrar, Straus

& Giroux, |

Casa Mariana

Casa Mariana

|

Side View of Casa Mariana

|

|

View

of Ouro Preto from Casa Mariana

|

Federal University of Ouro Pret

|

| The painting

and the photos credit: Department

of English, UNC-Chapel Hill |

TOP

|

| |

Bishop

and Psychobiography Bishop

and Psychobiography |

| |

- Bishop's

experience's of loss

- Her

father died when she was eight months old.

- Her

mother then was institutionalized. She died in a sanatorium

in May 1934.

- Bob

seaver committed suicide because she refused to marry him.

- Kita

took an "'accidental' overdose" upon their reunion in Yew York in 1967.

Brett Miller's Life and the Memory of It qut in MaCabe 253.

- MaCabe's interpretation of "One

Art":

"The poem reveals a struggle for mastery that will never be

gained. We can only make loss into therapeutic

play. One does try to master loss, but Bishop recommends that

we recognize our powerlessness and play with the condition of loss: the

blurring and splitting of presence and absence, being and nonbeing.

Bishop's "art of losing" resembles what

Freud in Beyond the Pleasure Pinciple calls the

rule of "fort-da" (gone/there), after a game his grandson constructed

in his mother's absence. . . . " (27)

- "Sestina"

--

To understand and

appreciate the poem, we need to understand

- How

Bishop weaves the six key words (child, grandmother, stove, house,

almanac, and tears) into the complicated pattern of sestina.

- How

the six elements develop and get different meanings in the poem.

As Ryan puts it very nicely, "[the] form

of the poem prescribes a repetition and displacement of

its key words that is reflective of the way grief

travels from one sign or object to another, moving away from and around

the original loss tha cannot be named except as 'it'" (42).

In other words, without naming or explaining the source of sadness, the

poem shows how the grandmother and the child respectively deal with

their losses by finding an indirect way to express and

transform their sadness. While Lacan thinks that our desire

can never be satisfied and we always need to replace the desired object

with something else on a metonymic chain, what Bishop shows here is the

cathartic process whereby the original sadness gets cleansed away or

transformed.

For

instance, tears gets replaced by rain, steam on the tea-kettle, tea,

button, moons (the passing of time) till finally it becomes something

to plant (bury)out of which something more productive might come.

Reference:

MaCabe,

Susan. Elizabeth Bishop: Her Poetics of Loss.

Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania UP, 1994. (Highly recommended)

- MaCabe's

approach:

"A

psychoanalytic perspective toward loss is

invoked through Freud; with Lacan, I am able to link the experience of

loss with writing. I supplement my use of the French

postmodern feminists Kristeva and Cixous, who invoke the possibility of

a distinctly feminine writing, with a variety of Anglo-American

feminists such as Chodorow, Oxtriker, Miller, Gilligan, Butler, Flax,

as they diversely approach issues associated with women's writing and

feminist philosophy" (xix)

Ryan,

Michael. Literary Theory : A Practical Introduction.

MA: Blackwell, 1999.

TOP

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|