| |

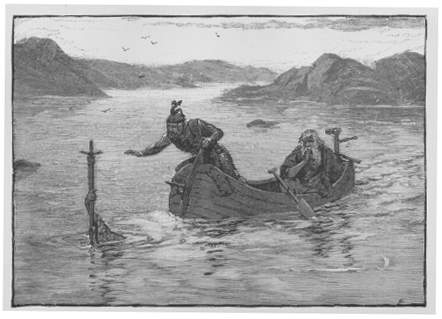

Source: http://www.lib.rochester.edu/camelot/images/bkaexc.htm

The Morte Darthur was finished,

as the epilogue tells us, in the ninth year of Edward IV., i.e. between

March 4, 1469 and the same date in 1470. It is thus, fitly enough, the

last important English book written before the introduction of printing

into this country, and since no manuscript of it has come down to us it

is also the first English classic for our knowledge of which we are

entirely dependent on a printed text. Caxton's story of how the book

was brought to him and he was induced to print it may be read farther

on in his own preface. From this we learn also that he was not only the

printer of the book, but to some extent its editor also, dividing

Malory's work into twenty-one books, splitting up the books into

chapters, by no means skilfully, and supplying the "Rubrish'' or

chapter-headings. It may be added that Caxton's preface contains,

moreover, a brief criticism which, on the points on which it touches,

is still the soundest and most sympathetic that has been

written.

Caxton

finished his edition the last day of July 1485, some fifteen or sixteen

years after Malory wrote his epilogue. It is clear that the author was

then dead, or the printer would not have acted as a clumsy editor to

the book, and recent discoveries (if bibliography may, for the moment,

enlarge its bounds to mention such matters) have revealed with

tolerable certainty when Malory died and who he was. In letters to The

Athenaeum in July 1896 Mr. T. Williams pointed out that the name of a

Sir Thomas Malorie occurred among those of a number of other

Lancastrians excluded from a general pardon granted by Edward IV. in

1468, and that a William Mallerye was mentioned in the same year as

taking part in a Lancastrian rising. In September 1897, again, in

another letter to the same paper, Mr. A. T. Martin reported the finding

of the will of a Thomas Malory of Papworth, a hundred partly in

Cambridgeshire, partly in Hunts. This will was made on September 16,

1469, and as it was proved the 27th of the next month the testator must

have been in immediate expectation of death.

It

contains the most careful provision for the education and starting in

life of a family of three daughters and seven sons, of whom the

youngest seems to have been still an infant. We cannot say with

certainty that this Thomas Malory, whose last thoughts were so busy for

his children, was our author, or that the Lancastrian knight discovered

by Mr. Williams was identical with either or both, but such evidence as

the Morte Darthur offers favours such a belief. There is not only the

epilogue with its petition, "pray for me while I am alive that God send

me good deliverance and when I am dead pray you all for my soul," but

this very request is foreshadowed at the end of chap. 37 of Book ix. in

the touching passage, surely inspired by personal experience, as to the

sickness "that is the greatest pain a prisoner may have"; and the

reflections on English fickleness in the first chapter of Book xxi.,

though the Wars of the Roses might have inspired them in any one, come

most naturally from an author who was a Lancastrian knight.

If

the Morte Darthur was really written in

prison and by a prisoner distressed by ill-health as well as by lack of

liberty, surely no task was ever better devised to while away weary

hours. Leaving abundant scope for originality in selection,

modification, and arrangement, as a compilation and translation it had

in it that mechanical element which adds the touch of restfulness to

literary work. No original, it is said, has yet been found for Book

vii., and it is possible that none will ever be forthcoming for chap.

20 of Book xviii., which describes the arrival of the body of the Fair

Maiden of Astolat at Arthur's court, or for chap. 25 of the same book,

with its discourse on true love; but the great bulk of the work has

been traced chapter by chapter to the "Merlin" of Robert de Borron and

his successors (Bks. i.-iv.), the English metrical romance La Morte

Arthur of the Thornton manuscript (Bk. v.), the French romances of

Tristan (Bks. viii.-x.) and of Launcelot (Bks. vi., xi.-xix.), and

lastly to the English prose Morte Arthur of Harley MS. 2252 (Bks.

xviii., xx., xxi.). As to Malory's choice of his authorities critics

have not failed to point out that now and again he gives a worse

version where a better has come down to us, and if he had been able to

order a complete set of Arthurian manuscripts from his bookseller, no

doubt he would have done even better than he did! But of the skill,

approaching to original genius, with which he used the books from which

he worked there is little dispute.

Malory

died leaving his work obviously unrevised, and in this condition it was

brought to Caxton, who prepared it for the press with his usual

enthusiasm in the cause of good literature, and also, it must be added,

with his usual carelessness. New chapters are sometimes made to begin

in the middle of a sentence, and in addition to simple misprints there

are numerous passages in which it is impossible to believe that we have

the text as Malory intended it to stand. After Caxton's edition

Malory's manuscript must have disappeared, and subsequent editions are

differentiated only by the degree of closeness with which they follow

the first. Editions appeared printed by Wynkyn de Worde in 1498 and

1529, by William Copland in 1559, by Thomas East about 1585, and by

Thomas Stansby in 1634, each printer apparently taking the text of his

immediate predecessor and reproducing it with modifications. Stansby's

edition served for reprints in 1816 and 1856 (the latter edited by

Thomas Wright); but in 1817 an edition supervised by Robert Southey

went back to Caxton's text, though to a copy (only two are extant, and

only one perfect!) in which eleven leaves were supplied from Wynkyn de

Worde's reprint. In 1868 Sir Edward Strachey produced for the present

publishers a reprint of Southey's text in modern spelling, with the

substitution of current words for those now obsolete, and the softening

of a handful of passages likely, he thought, to prevent the book being

placed in the hands of boys. In 1889 a boon was conferred on scholars

by the publication of Dr. H. Oskar Sommer's page-for-page reprint of

Caxton's text, with an elaborate discussion of Malory's

sources.

Dr.

Sommer's edition was used by Sir E. Strachey to revise his Globe text,

and in 1897 Mr. Israel Gollancz produced for the "Temple Classics'' a

very pretty edition in which Sir Edward Strachey's principles of

modernisation in spelling and punctuation were adopted, but with the

restoration of obsolete words and omitted phrases. As to the present

edition, Sir Edward Strachey altered with so sparing a hand that on

many pages differences between his version and that here printed will

be looked for in vain; but the most anxious care has been taken to

produce a text modernised as to its spelling, but in other respects in

accurate accordance with Caxton's text, as represented by Dr Sommer's

reprint. Obvious misprints have been silently corrected, but in a few

cases notes show where emendations have been introduced from Wynkyn de

Worde -- not that Wynkyn had any more right to emend Caxton than we,

but because even a printer's conjecture gains a little sanctity after

four centuries. The restoration of obsolete words has necessitated a

much fuller glossary, and the index of names has therefore been

separated from it and enlarged. In its present form the index is the

work of Mr. Henry Littlehales.

TOP

|

| |

Source:

http://www.lib.rochester.edu/camelot/images/hjfsword.htm

John Spiers, 'Malory's "Morte

D'Arthur"', in The New Pelican Guide to English Literature 1. Medieval

Literature, 1997. John Spiers was Reader in English at Exeter

University. Malory's prose Morte D'Arthur

(printed by Caxton 1485) is best approached after a reading of the

English Arthurian verse romances which preceded it, rather than from

the poetry of Tennyson and other poets who have since used it as a

source. As Professor Vinaver has shown in his edition of the works of

Malory, what is really a succession of separate prose romances has been

given an appearance of unity, of being one 'book', by the way they were

edited and printed by Caxton (under the misleading title of Morte

D'Arthur). There could be no greater contrast than that between

Malory's exceedingly 'literary' fifteenth-century prose romances and

the English verse romantics or lays of the thirteenth and fourteenth

centuries. Malory's prose, with all its seeming simplicity - it is a

stylisation of earlier medieval prose - is in some respects the nearest

thing in medieval English to the prose of Walter Pater. There is a tone

of fin de siecle about Malory's book.

At the end of the Middle Ages and the end of a long efflorescence of

medieval romance in many languages, Malory endeavoured to digest the

Arthurian romances into English prose, using as his source chiefly an

assortment of French Arthurian prose romances. But this traditional

material has not been organised so as to convey any coherent

significance either as a whole or, for the most part, even locally.

Malory persistently misses the point of his wonderful material. (This

may be partly because he had no access to the earlier and better

sources - if we except the fourteenth-century English alliterative

Morte Arthur- and was dependent, or chose to be dependent, on his

French prose romances.) The comparison with Sir Gawain and the Green

Knight is in this respect -as, indeed, in nearly all respects - fatally

damaging to Mallory's Morte D'Arthur. . . What is it, then, that

constitutes the charm of the book, that draws readers back to parts of

it again? Partly, it is the 'magic' of its style - those lovely elegiac

cadences of the prose, that diffused tone of wistful regret for a past

age of chivalry, that vague sense of the vanity of earthly things. Yet

the charm of the prose is a remote charm; the imagery is without

immediacy; there is a lifelessness, listlessness, and fadedness about

this prose for all its (in a limited sense) loveliness. There is also

the fascination of the traditional Arthurian material itself, even

though we feel it is not profoundly understood. The material fascinates

the reader in spite of Malory's 'magical' style which seems to shadow

and obscure rather than illuminate it. Malory's Grail books, for

example, include some of the most fascinating of his original material.

We find here once again the Waste Land, the Grail Castle, the Chaple

Perilous, the Wounded King, and so on but reduced to little more than a

succession of sensations and thrills. The recurrent appearance of the

corpse or corpse-like figure on a barge and the weeping women -

fragments of an ancient mythology though they are - become in Malory

merely tedious after a number of repetitions, and the final effect is

one of a somewhat morbid sensationalism.

Some qualifications of these structures should be made on behalf of the

last four books of Caxton's Malory, which may be felt to have an

impressive kind of unity of their own. The lawless loves of Lancelot

and Guinevere, the break-up of the fellowship of the Round Table

through treachery and disloyalty, the self destruction of Arthur's

knights and kingdom in a great civil war, the last battle and death of

Arthur, and the deaths of Lancelot and Guinevere have, as they are

described, a gloomy power, and are all felt as in some degree related

events. This set of events appears to have been deeply felt by Malory,

partly as a reflection of the anarchy and confusion of the contemporary

England of the War of the Roses.

(Source: Penguin

Classic)

TOP

|