|

|

|

|

| Edward Estlin Cummings |

| ��w�ءD�㴵�S�L�D�d���� |

| �Ϥ��ӷ��Ghttp://www.english.uiuc.edu/maps/poets/a_f/cummings/cummings.htm |

| �D�n�����GPoem |

| ��ƴ��Ѫ̡GFr.Pierre E.Demers/�ͼw�q����;Dr. Edward Vargo |

| ����r���GModern American Poetry |

|

|

|

|

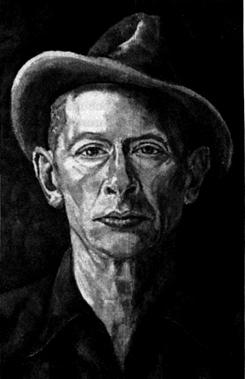

Edward Estlin Cummings

1894-1963

|

| �@ |

Biography Biography

Cummings' Technique Cummings' Technique

- Use of Capitalization & Parenthesis

- Use of Adverbs & Verbs as Nouns - Word

Order

- Creative Use of Cliches

- Use of Typographical Design

- Use of Space

- Use of Telescoped words

- Combined Use of Devices

- Use of Punctuation

�@

|

| �@ |

�@ |

| Biography |

| �@ |

mOOn Over tOwns mOOn

whisper

less creature huge grO

pingness�@

whO perfectly whO

flOat

newly alOne is

dreamest�@

oNLY THE MooN o

VER ToWNS

SLoWLY SPoUTING SPIR

IT

The

mere typography, of this poem identifies it as the work of e e cummings

(as he liked to print his name). Yet this is one of the more tame of

his poems. Another begins:

(b

eL1

s?

bE

One

of the most famous, entitled "r-p-o-p-h-e-s-s-a-g-r," on a grasshopper,

is a typographical orgy of spacing, punctuation, capitals, small

letters, line divisions, and anagrams of the grasshopper, not to

mention the chaos of grammar and word order. Cummings the poet was also

a professional painter and gave extreme care to the visual format of

his poems. He was also a rabid circus fan and wished his playful use of

words and their physical appearance on the page to be as clever as the

pratfalls of a clown. He meant to surprise and to amuse. He always

surprised but did not always amuse the staid critics of poetry. Some he

infuriated.

Cummings

began his adult life as a prankster who soon suffered from those who

did not enjoy his sense of humor. After gradating with an M.A. from

Harvard in 1916, the son of a well-known Congrationalist minister, he

left for France in 1917. In the company of another prankster from

Columbia University, William Slater Brown, he joined an American

ambulance corps during World War I. Brown began writing letters home

asserting a widespread despondency in the French army. His prediction

of imminent mutiny and even revolution failed to amuse the official

censors of mail who soon had the two young men arrested as spies. Since

the irresponsible prank was the work of Brown, Cummings could have been

immediately released if he had been willing to swear, to the

satisfaction of the French authorities, that he only felt hatred for

all Germans without exception. Cummings was already a worshipper of

true individual feelings and refused to comply to such a condition for

his liberation. He spent three months in prison for treasonable

correspondence after which he sailed for home. From this experience

came his first work, a novel he called The Enormous Room

foreshadowing the literature of the absurd that was to spread after the

second world war.

After

publishing a volume of poems, Tulips and Chimneys,

in 1923, he returned to Paris to study painting while still writing

poetry. When he returned to America two years later he found that his

novel and book of poems had already made him famous, and the Dial prize

for poetry was offered to him. From then on he devoted all his time to

poetry and painting, always playful, the complete individualist, a

lover of life and art. Besides Tulips and Chimneys

his collections of poems include &[AND](1925),

XLI Poems (1925), is 5(1926), W [ViVa](1931),

no thanks (1935), 50 POEMS

(1940), 1*1 (1944), Xaipe (1950). All these were

collected by definite choice in a book entitled, Poems

1923-1954. In 1927, he wrote his first play, Him;

it might well be considered "one of the first successful attempts at

what is now called the theater of the absurd," with a Beckett-like

dialogue:

Him: What are the audience doing?

Me: They're pretending that this room and you and I are real.

Him: I wish I could believe this.

Me: You can't.

Him: Why?

Me: Because this is true.

Anthropos

followed in 1930. It is a criticism of what people call progress at the

expense of real life. Tom (1935) is a ballet

based on Uncle Tom's Cabin. Santa Claus

(1946) is a blank verse play written after Hiroshima; it attacks

science and scientific habits of thought: "Knowledge has taken love out

of the world/and all the world is joyless joyless joyless." In 1952, he

delivered a series of lectures at Harvard, later published under the

title i: six nonlectures.

In

all these works there is real delight in the absurd, the comical, even

the clownish. Yet a closer look into the content of the poems reveals a

more serious purpose than mere amusement. By distorting the physical

appearance of the words and phrases of a tired language, Cummings

forces the reader's attention back to their real meaning. As appears in

the "mOOn" poem above, by relating the appearance of words and their

meaning, he achieves a sort of impact on the reader's consciousness not

unlike the impact of Chinese ideograms.

When

the door of meaning has once been opened for us, quite an attractive

interior is revealed. Already in The Enormous Room,

the main themes of Cummings' poetry are present. It is a celebration of

the joy of life in the midst of the waste land of modern times. The

novel relates how in conditions degrading the human, striving to

extinguish the personal, stifling the individual, etc, life is still

made liveable by the "triumphant survival of distinctiveness, of

idiosyncrasy, of all those elements of character and behavior that

separate the individual from the 'unperson'." Cummings' poetry is a

celebration of the triumph of life. The freshness of language mirrors

the freshness of apprehension, of spontaneity, of instinctive response

to existence:

i thank You God for most this amazing

day: for the leaping greenly spirits of trees

and a blue true dream of sky; and for everything

which is natural which is infinite which is yes�@

(i who have died am alive again today

a

and this is the sun's birthday; this is the birth

day of life and of love and wings; and of the gay

great happening illimitably earth)

�@

how should rasting touching hearing

seeing

breathing any - lifted from the no

of all nothing - human merely being

doubt unimaginable You?�@

(now the ears of my ears awake and

now the eyes of my eyes are opened)

Fullness

of life means fullness of awareness of the present, forgetting the

past, ignoring the future; it is a full dedication to what he

repeatedly calls the "illimitable Now and Here." His philosophy is that

of an unconditional yes said to the present. Any other way of living is

a nonlife:

Wherelings whenlings

(daughters of ifbut offspring of hopefear

sons of unless and children of almost)

never shall guess the dimension of�@

him whose

each

foot likes the

here of this earth

whose both

�@

eyes

love

this now of the sky

The

"wherelings whenlings" are the dead afraid to be born; in other words,

the unpeople, and "mostpeople" are unpeople: "by some fatal, some

incomparably fatal accident" only a few men have a soul; only these can

live their souls. His anti-intellectualism verges on the fanatic: "The

more we know the less we feel," he writes in one of his letters, while

one of his poems begins "he does not have to feel because he thinks."

The human body, and essential element of the person, must be

absolutely, fearlessly alive. Naturally then, Cummings wrote the

greatest number of erotic poems of all 20th-century poets. He also

wrote some of the most musical lyrics of the age:

All in green went my love riding

on a great horse of gold

into the silver dawn.

Of

course the speaker in Cummings' poems, the celebrater of life, of joy,

of love, of the illimitable now is a Persona, a

creation of Cummings' imagination. Yet, like Whitman, Cummings tried to

live his Persona. His letters often refer to his

anxiety over financial problems and to his depressions, the "dying

night" of his soul at the time of the failure of his marriage. But he

would soon bounce back to life, joy, and love. His determination to BE,

to live his soul, always won. As he wrote in the introduction to his

collection, New Poems:

The poems to come are for you and for

me and

are not for mostepeople.... Take the matter of

being born. What does being born mean to

mostepeople?... If mostpeople were to be born

twice they'd improbably call it dying... you and

I... we can never be born enough. We are

human beings; for whom birth is a supremely

welcome mystery, the mystery of growing:

the mystery which happens only and whenever

we are faithful to ourselves.

Because

of the novelty and experimental nature of his poems. Cummings will

always remain a controversial poet. His prominence is assured, though,

because his ideosyncrasies are purposeful, his apparent illogicality

meaningful, and his language clear, precise, and melodic.�@

TOP

|

| Cummings'

Technique |

| �@ |

Cummings' strange technique may

perhaps be best explained by examining it progressively from the poems

which depart only slightly from traditional verse to the most

idiosyncratic and puzzling forms.

�@

|

| A.

Use of Capitalization & parenthesis |

| �@ |

"My Sweet Old Etcetera" contrasts the

abstract, conventional idealism of the speaker's family towards war and

the realism of his actual dying in the mud dreaming of love and

conception of life. The stanzas are arranged in love and conception of

life. The stanzas are arranged in a 2-3-2-4-2-5-2-6 (3-3) line pattern.

The pronoun "i," the proper name "isabel," the first letter of each

line are not capitalized while "Your" and "Etcetera" in the last two

lines use the upper case. Cummings' use of capital letters for stress

or other effects preclude their conventional use - "Your smile" and

"your Etcetera" achieve thus an impact on the reader's consciousness.

Furthermore, this unconventional use of capitals contribute to the

theme of the poem which mocks the conventional attitude towards death

in the field of honor. The parentheses enfold the secret thoughts of

the speaker as opposed to the objective scene of the rest of the poem.

The separation of "et" and "cetera" which both divide and unite the 3-3

line pattern of the last stanza slows down the rhythm and suggests

either the breaking off of life of the last gasp of the dying.

TOP

|

| �@ |

B. Uses of Adverbs

& Verbs as Nouns - Word Order |

�@ |

| �@ |

"Anyone Lived in a Pretty

How Town" with its conventional enough four line stanzas and occasional

rhymes intensifying the rhythm of the stanzas where they appear,

presents a peculiar use of the parts of speech. Expressions like "how

town," "he sang his didn't," "he danced his did," "they said their

nevers," where adverbs and verbs are used as nouns, give freshness,

force, and new life to worn out words. They are clear in spite of, or

rather because of, their deliberately faulty grammar. In the context of

the whole poem the how-town is the community where what counts is how

to conform to the requirements of society and become somebody, and not

how to live fully from the spontaneous springs of love and life within

us. In the larger context of Cummings' poetry, to live in the fullness

of one's possibility for intense living, sensations, and feelings is

perhaps the most frequent and profound theme. Cummings always equates

success in life with a life lived in harmony with the deepest natural

instincts of man; to chose to be in his uniqueness and become "anyone"

rather than to play the social game and become "someone." This is the

only way man can feel alive and enjoy the gift of life in an

industrial, conformist culture. In his other writings, Cummings exalts

the being that is,

what he calls "an IS," one that exists

fully, the realizes the full potentialities of life within oneself. In

such a context, expressions like "they sowed their isn't," "they said

their nevers" applied to the someones and the everyones in the

how-town, acquire concentrated force. The theme of the poem is really

to be or not to be, that is , in Cummings' parlance, to be an "is" or

an "isn't."

"Anyone"

is an "is" because he can love, and consequently be loved, his life is

a dance in harmony with the rhythm of nature. The contrasts between

life and death are carefully arranged in the poem. "Anyone" lived

in the dead how-town, "noone" loved him, while women and men in the

town cared for "anyone" not at all. "Anyone's" any was all to "noone";

she laughed his joy and cried his grief, while loveless "someones"

laughed their "everyone's" crying; "anyone" danced his did, the

"someones" did their dance, and so on.

Another

peculiarity of the poem is the syntax of a line like "with up so

floating many bells down" in which the order of words seems to be that

of a foreign language. Cummings often distorted the normal order of

words to force attention by having the reader re-order the words

properly in his mind and to preserve a fitting rhythm. The normal

order, with so many bells floating up and down, would be a flat

insignificant statement.

TOP

|

�@ |

| C.

Creative Use of Cliches |

| �@ |

A third remarkable device used by

Cummings in this poem is the renewal of cliches. "Little by little" is

refreshed by the use of "more by more," a pattern of speech he prolongs

into "when by now," and "tree by leaf," in which "more" is multiplied

by "more"; "when," suggesting sometime in the past or the future is

replaced by the "now"; the tree is always with leaf in a permanent

spring of renewed life for "anyone" and "noone." Further on, the poem

has a similar enumeration in which it progresses from cliches to

original expressions - side by side, little by little, was by was, all

by all, deep by deep, earth by april, wish by spirit, if by yes - a

veritable litany of praises for those buried there who have truly

lived. "Anyone" and "noone" have truly lived (was by was), fully (all

by all), deeply (deep by deep), in harmony of desire and spirit,

unconditionally, a spontaneous yes said to life (if by yes).

"My

Father Moved through Dooms of Love" may very well be described as an

elaboration of the life of the "anyone" in the poem just treated. The

poem has the same stanza form, makes a similar use of rhyme, and of

parts of speech - "through sames of 'am' through haves of 'five'"

which, in a single line, suggest much the father's constant fidelity

and enrichment of himself through giving in love. He offers

immeasurable "is," he "lived his soul."

TOP

|

| D.

Use of Typographical Design |

| �@ |

"L(a" illustrates another device of

Cummings' to refresh the meaning of worn out words and enrich them with

further meanings. The theme of the poem is simple enough - the

correspondence between an external scene and a state of mind -

loneliness (a leaf falls). This poem cannot be read aloud, it has to be

seen. Furthermore, the typographical presentation is a design

suggesting a falling leaf. To the traditional combination of sound and

sense Cummings adds sight.

The

insertion of the parenthesis in the middle of the word suggests the

simultaneity of the scene and the feeling. Cummings often tries to do

away with the sequence of time and suggest the present in all its

complex now. Of course a poem will always be a sequence in time; yet,

the typographical design and the inserted parenthesis do achieve a

suggestion of the instantaneous and simultaneous.

This

device also allows the poet to break up words and wring all kinds of

connotations out of them. Modern language is a tired language so

overused by propaganda, publicity, cheap novels, and songs that words

have lost much of their strength and freshness. In this poem, Cummings

breaks the word loneliness into one, 1 (the letter, "1," and the

number, "one," being the same symbol ["1"] on the typewriter), and

"iness" which could be interpreted as "i-ness," the preoccupation with

the I, the ego, or in-ness in the sense of introversion.

Often

in Cummings' poems the unusual and idiosyncratic is framed in a rather

formal pattern; in this case, the 1-3-1-3-1 stanza pattern. Cummings'

individualism is never wild but based on certain constants of human

nature: his poems almost always reveal, on lose analysis, some kind of

regular pattern, mostly in their stanzaic forms.

TOP

|

| E. Use of Space |

| Cummings, who was a painter and an

admirer of Picasso, learned a further device from modern painting,

namely, the artistic use of empty space. "In Just-" offers a clear

example of it. The poem presents the dynamic image of children at play

just when springtime appears while the balloon-man approaches from

afar; he is rushed to by the children and then vanishes in the

distance. In this renewal of life in Spring, the balloonman is

goat-footed like Pan, the god of forests, pastures, and flocks. His

coming, passing, and vanishing is suggested by the various arrangements

of space between the words "whistles far and wee," a refreshed use of

the old cliches "far and wide" or "far and away." These spaces are like

musical rests controlling the speed of the reader's voice. The stanzaic

pattern is again regular: 4-1-4-1-4-1-4, but each stanza uses various

means of stressing certain words. "Just" is capitalized; "spring"

isolated three times; the importance of "goat-footed" and all its

implications is impressed upon us by its splendid isolation, followed

by the capitalization in "balloonMan." This provokes all sorts of

considerations on the decay of life from the sacred to secularization.

It makes the whole scene a kind of consecration of Spring, from which

the dead adults of the poem "Anyone Lived in a Pretty How Town," are

absent and which only the children are apt to understand.

TOP

|

| F.

Use of Telescoped Words |

|

In this

poem Cummings also uses a device that is the obverse of breaking-up

words as he did in "1(a": he telescopes several words into one

(eddieandbill, bettyandisbel) to convey a single impression. Cummings

was a creator of fresh word-clusters of extreme suggestive power:

"mudluscious," "puddle-wonderful" bring back to us the joys of our

childhood at play.

"Buffalo

Bill" uses the same devices to create effect-capitalization (Buffalo

Bill, Jesus, Mister Death), word isolation (defunct, stallion, Jesus,

Mister Death), word-telescoping (onetwothreefourfive,

pigeonsjustlikethat), word-clusters (watersmooth-silver), word spacing

(and what i want to know is), all contribute to a complexity of image,

feeling, and tone.

TOP

|

| G.

Combined Use of Devices |

|

A more extreme example of the

combined use of the devices seen so far, plus further sophistications

of technique, is offered in "R-p-o-p-h-e-s-s-a-g-r," the poem on the

grasshopper:

r-p-o-p-h-e-s-s-a-g-r

who

a)s

w(e loo)k

upnowgath

PPEGORHRASS

eringint(o-

aThe):1

eA

!p:

S

a

(r

rIvInG

.gRrEaPsPhOs)

to

rea(be)rran(com)gi(e)ngly

,grasshopper;

Here

not only the word order of a phrase, as in previous poems,but even the

letter order of a word is distorted in a series of unpronounceable

anagrams of the word grasshopper. Again the poem is for the eyes only.

The various letter order of the word grasshopper and their

capitalization suggest the various impressions that fill the brief

instant it takes to pass from the first impression of a long jumping

thing to the realization that it is a grasshopper. The use of hyphens

and capitals transmits this sequence of impressions - the hyphens

suggest a long indefinite thing and the solid capitals, something too

near and big to be distinguished; the alternation of small and capital

letters, the zigzagging flight; the proper order of small letters, the

final recognition.

The

word puzzle is easily solved, especially if one realizes that the

letters of three words ("r-p-o-p-h-e-s-s-a-g-r," "PPEGORHRASS" and

"gRrEaPsphOs), when unscrambled, all spell "grasshopper." The poem may

be laid out in a more conventional way thus:

r-p-o-h-e-s-s-a-g-r

[an unidentifiable motion]

who as we look up now, gathering into a

The PPEGORHRASS [some peculiar thing],

leaps, arriving

gRrEaPsPhOs [the letters of the thing scrambled again]

to become rearrangingly a

grasshopper.

The

parentheses may have several interpretations: isolating the speaker's

reaction(a, e, 1oo, o-a, The [(a definite article showing the beginning

of the recognition of something definite]); describing with small and

capital letters his impression of the motion together with a scraping

sound, or expressing simultaneity ("become rearrangingly").

"Leaps"

is a key word whose every letter is isolated for stress. The whole

typographical design of the poem is not so much, as in "L(a," an

ideogram of a hopping grasshopper, but rather an abstract

representation of the observer's sense impressions.

TOP

|

| H. Use of Punctuation |

|

A new device to

be observed in this poem is the peculiar use of punctuation. Since

space between words is significant, the punctuation marks themselves

are not accompanied by spaces as in the conventional way. Space itself

is a sort of punctuation. Here the colon isolates "leaps" and the

exclamation mark does suggest an exclamation in the middle of the leap.

The comma seems to take the place of the indefinite "a" which would

destroy the effect of the previous "The." The final colon suggests that

this motion is not the end, but that another will follow. The period

before "gRrEaPsPhOs" seems to make of the anagram a parenthesis within

a parenthesis. This poem may have little poetic value, but it does

illustrate all the devices of a technique which aims at conveying,

through the medium of the written language, fullness of awareness.

Cummings'

rather peculiar use of so many unusual techniques in his concise poems,

makes them particularly difficult to explain in a brief way. For this

reason, many of the annotations are necessarily long and somewhat

cumbersome.

Unfortunately,

our analyses tend to leave out what is most important and charming is

Cummings: humor, which is a form of joy. Cummings is basically a

humorous poet and to look upon his poems with academic seriousness is

to miss their delightful flavor. But if the Study Guide treatment runs

the risk of obscuring this lively and subtle quality, we rely on our

reader's own good sense of humor to compensate.

TOP

|

| �@ |

|

|

|

|