These notes refer to the Vintage paperback edition of the novel (New York, 1990)

Joseph C. Murphy

Prologue. At Rome

The elegant dinner hosted by the Spanish Cardinal Garcia Maria de Allande provides a perspective on the New World missions from the standpoint of Rome, the center of the Roman Catholic Church. The sophisticated and privileged Spanish, Italian, and French Cardinals little understand the realities faced by the visiting Bishop Ferrand, a missionary in the Great Lakes region. For the Italian Cardinal the missions are merely a source of trouble and a financial drain. The Spanish Cardinal seems primarily interested in recovering his family's lost El Greco, and would prefer to take his view of American Indians from the novels of James Fenimore Cooper, rather than from direct reports. Ferrand struggles to express the importance of the New Mexico territory, recently annexed by the United States from Mexico (at the close of the Mexican War) and soon to be elevated to an Apostolic Vicarate (a territory administered by a vicar [delegate] of Rome, who has the powers of a bishop). The huge and physically awesome territory, which will later become a formal diocese,

|

| Jehan Vibert, The Missionary's Adventures http://www.metmuseum.org/Works_Of_Art/viewOne.asp?dep= isHighlight=0&viewmode=1&item=25.110.140 |

| Top |

Book One. The Vicar Apostolic

1.

The Cruciform Tree. This chapter opens with the"geometrical nightmare" of many uniform

"conical red hills""somewhere in central New Mexico" (17)°Xcontrasting sharply with the highly civilized and established Italian villa of the Prologue. The"solitary horseman" is Jean Marie Latour (based on Jean Baptiste Lamy, the first Bishop of Santa Fe) introduced in the Prologue as"a man of severe and refined tastes" (13), here described as one"sensitive to the shape of things" (18). Cather describes the abstract, geometrical features that attracted many artists and writers to New Mexico during the 1910s and 20s. However, for Cather°¶s priest protagonist, lost and dehydrated, this landscape requires some transcendent meaning, and he finds this in the juniper tree resembling"the form of the Cross" (18). Latour°¶s perception of a religious symbol amid the geometrical chaos foreshadows his future work, which will be to make religious meaning legible in an overwhelming and sometimes alien landscape. At this point, Latour can only approach the landscape through the figure of the Cross°Xprojecting his consciousness of his own suffering onto the suffering of Christ (20). Like Christ in Jerusalem, Latour has been rejected by his own flock, turned out by his own city of Santa Fe: "He was a Vicar Apostolic, lacking a Vicarate" (20). He is heading to Durango, Mexico, to get the necessary documents to establish his authority in Santa Fe.

2.

Hidden Water. This chapter deepens our understanding of Latour and of the New Mexican

culture where he will work. Stumbling upon the settlement called Agua Secreta ("Hidden Water"), Latour is saved

from dehydration, but confronts in miniature the difficulties that he will face as a bishop:"This settlement was his Bishopric in miniature; hundreds of square miles of thirsty desert, then a spring, a village, old men trying to remember their catechism to teach their grandchildren" (32). Latour will face not only the challenge of space°Xthe vastness of his diocese°Xbut also the narrowness and prejudices of his flock°¶s beliefs. The Mexican family here view Americans and Protestants as"infidels." They have a taste for miracles°Xfor example, the grandfather thinks Latour was led to them by the Virgin Mary (25)°Xand for religious statues. Notice how Latour°¶s religious views are more liberal and intellectual: he accepts Protestants, and sees God working within the laws of Nature, rather than against Nature (29). Still, Latour respects this family°¶s loving care, their religious statues, and their"refuge for humanity" in the desert (31).

| Statue of Archbishop Lamy in front of the Cathedral he built. Photograph Copyright 2005 by Joseph C. Murphy |

3.

The Bishop Chez Lui. The time is Christmas several months after the previous chapter, and

nine days after Latour's return from old Mexico. Latour is"chez lui" (at home) writing to his family in Auvergne, France, and awaiting the Christmas dinner prepared by his vicar Father Joseph Vaillant (based on the historical Joseph P. Machebeuf). This chapter conveys the cultural complexity of the French priests' lives in New Mexico. We see the primitiveness of the handmade adobe walls and wooden furniture, and the rough habits of the local cowboys, but also the refinement of the civilization they left behind in France, which Vaillant tries his best to maintain in the Christmas meal, using local ingredients. The priests ' attention is divided between their loyalties to the American soldiers (the civil authorities), their service to the Mexican people, and their memories of their childhood in France. Consequently, they switch between the English, Spanish, and French languages, as the occasion requires. Cather describes Father Vaillant as an ugly man whose huge capacity for action is not manifest in his slight body (37-38). Compare this description to that of Father Latour (18-19), whose refinement is very evident in his appearance and manner. Here and elsewhere in the novel, what relationship does Cather establish between the physical appearance and spiritual qualities of her characters?

4.

A Bell and a Miracle. Cather continues to study the contrasts between Latour and Vaillant.

Latour likes the idea that there may be some Moorish (Muslim) silver in the old bell Vaillant found, but Vaillant sees this idea as"belittling" (45). It is Vaillant who is"deeply stirred" by a visiting priest's story of the appearance of

the Virgin Mary to a peasant in Guadalupe, Mexico. Latour, however, suggests (consistent with his earlier reflections [29]) that miracles are not visitations of"power" from far away, but rather a case of"our perception being made finer, so that for a moment our eyes can see and our ears can hear what is there about us

always" (50). In both instances, Vaillant's religious views are simple and traditional, whereas Latour's are more sophisticated and pragmatic. Note, incidentally, Cather's jumbling of time in the novel: the events in this chapter take place the day after Latour's return from Mexico, eight days before the events of the previous chapter.

|

| The miraculous image of Our Lady of Guadalupe http://www.unitypublishing.com/ protector.html |

| Top |

Book Two. Missionary Journeys

1.

The White Mules. One convention of the adventure story, whether of the medieval knight,

Western cowboy, or postmodern spy, is the ritual scene where the hero is presented with a prize vehicle°Xthe horse or automobile that becomes a signature component of his character and deeds. So in this chapter, the nineteenth-century New Mexican priest Vaillant receives (through some crafty manipulation of Manuel Lujon's religious devotion) the white mules Contento and Angelica, who will carry Vaillant and Latour on many missionary adventures. Note that it is Vaillant, the greater man of action, who receives the mules, and Vaillant who takes both mules with him when he parts ways with Latour in Book Eight (252-53).

2.

The Lonely Road to Mora. This chapter continues the adventure-story format, with the two

mounted priests pushing through a storm and landing at the door of Buck Scales, who is later proven a mass murderer. Remarkably, we see the Bishop draw his pistol, like a gunfighter (69). However, these events are at some level antiheroic. Latour's pistol is wet and probably wouldn't fire (68). The priests do not immediately rescue the abused wife Magdalena. Instead, they save themselves, and Magdalena scrambles after them through the storm. Despite these misadventures, Magdalena is saved, Scales is brought to justice, and Latour strikes up a lifelong friendship with the archetypal Western hero Kit Carson (known as"Christobal" in Spanish). Kit Carson was an actual historical figure; Cather uses his real name in the novel.

| Top |

Book Three. The Mass at Acoma

1.

The Wooden Parrot. In this book Latour takes a tour, accompanied by the Indian guide Jacinto,

to the missions of Isleta, Laguna, and Acoma. Their first stop is the city of Albuquerque, where the B ishop is hosted by the gambler priest Gallegos, whom Latour finds"engaging" as a man but"impossible" as a priest (83). In Isleta, Latour examines an old wooden parrot, a token of the reverence pueblo peoples extend to this bird. Like the saint statue and the old bell, the wooden parrot is one of the many physical objects Latour encounters that communicate a richness of history and culture beyond words. Cather herself reflected on the churches of the Southwest:"They are their own story, and it is foolish convention that we must have everything interpreted for us in written language." Father Jesus of Isleta reports that the Indians of Laguna and Acoma are friendly (87)°Xcasting some doubt on Father Gallegos's characterization of the Acomas as difficult and deceptive (83).

2.

Jacinto. Here the relationship between the Bishop and Jacinto deepens through their shared

travels. The two talk briefly about Jacinto's family and about the landscape and the stars, but overall"silence... was their usual form of intercourse" (91). For Latour, this silence reflects the cultural divide between them:"There was no way in which he could transfer his own memories of European civilization into the Indian mind, and he was quite willing to believe that behind Jacinto there was a long tradition, a story of experience, which no language could translate to him" (92). The"Indian conception of language" is a mystery to Latour. He and Jacinto communicate in Spanish and sometimes in English, European languages that are part of Latour's civilization but, for that matter, are not native languages for him either.

3.

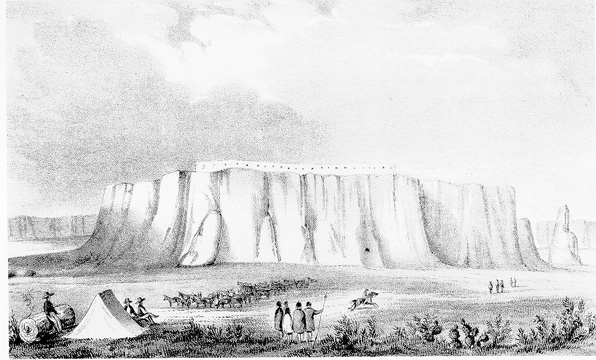

The Rock. This chapter continues to explore the problem of communication between Indians

and Europeans. The issue here is the physical setting°Xa country that"was still waiting to be made into a landscape." Landscape °Xa European concept°Ximplies arrangement and order, but what Latour sees is a scene

that is not yet"brought together," as if the Creator had not finished the job (94-95). Latour's perceptions of the land extend to the Acoma people as well: he sees them as"rock turtles on their rock," a people without the"glorious history of desire and dreams" that have developed European civilization (103). Saying Mass in the Acoma church, Latour feels a huge spiritual distance between himself and the Indians. Ironically, however, he reflects that"the old warlike church" itself, designed by the seventeenth-century Spanish missionaries (who commanded the Indians to build it), may be partly to blame. These missionaries"built for their own satisfaction, perhaps, rather than according to the needs of the Indians" (100-01). These criticisms of church architecture will be important to remember when Latour plans his own cathedral later in the novel. How do Latour's observations of other churches influence his plans for his own cathedral?

|

|

| James Abert, Pueblo of Acoma, 1846. http://www.uic.edu/depts/ahaa/classes/ah111/acoma1.jpg | The church at Acoma. Photo by David DeDene http://www.chrylab.com/acoma.html |

4.

The Legend of Fray Baltazar. This legend (a story-within-the-story) is told by Father Jesus of

Isleta. It dramatizes the consequences for missionaries who live for their own satisfaction, rather than for their people. Baltazar is a particularly tyrannical priest who oppresses the Acomas to satisfy his appetite for good food and drink. When his gluttony drives him to accidentally kill a clumsy Indian servant, his people turn on him and cast him off the mesa. Interestingly, although Baltazar is a kind of sensualist, he is courageous in death, and"retained the respect of his Indian vassals to the end" (113).

| Top |

Book Four. Snake Root

1.

A Night at Pecos. Latour teams up with Jacinto again, this time on a journey to rescue Vaillant,

who has fallen ill at Las Vegas (not the now-famous city in Nevada, but a city in New Mexico east of Santa Fe ). Latour meets Jacinto at his home in Pecos, a pueblo that is dying out and, as Cather's note indicates, was actually abandoned before the U.S. occupied the area (123). In her fictional account, Cather shows Pecos still barely functioning, perhaps as a dramatic image of the devastating effects of white diseases on Indian settlements, and also as an occasion to introduce two legends about the Indians: that they spent their energies keeping perpetual fire burning in the mountain, and that they sacrificed infants to a ceremonial snake. These legends are more likely grounded in Anglo-American romanticism about the Indians than in actual Indian customs. However, it is historically accurate, as Latour observes, that the Spanish conquistador Coronado and his men camped near Pecos and exploited the Indians in 1540-41. Reflecting on this dark history, Latour feels as if the wind were"blowing out of a remote, black past" (124).

2.

Stone Lips. This chapter, sitting near the center of the novel, describes Latour's most alienating

experience of Indian culture. A snowstorm forces the Bishop to take refuge with Jacinto in a secret cave used for Indian ceremonies. Entered through"two great stone lips" (126), the cave is likened to an orifice and a throat. Despite the resemblance of the cave to a"Gothic chapel" (a familiar European religious image), Latour immediately feels"an extreme distaste for the place," particularly its"fetid odour" (127). Jacinto's ritualistic behavior in the cave mystifies the Bishop. Consistent with its oral imagery (lips, orifice, throat), the cave is vibrating with the sound of an underground river that Latour hears as"one of the oldest voices of the earth" (130). Although Jacinto shares this sound with Latour, clearly the Indian can experience it in ways the Bishop cannot: late at night, Latour wakens to find Jacinto stretched against the rock,"listening with supersensual ear" (131). Jacinto's"puzzling behavior" (133), coupled with the legends he has heard, later prompts Latour to ask the trader Zeb Orchard about Indian religious ceremonies. Orchard underscores what Latour already feels:"No white man knows anything about Indian religion" (134).

| Top |

Book Five. Padre Martinez

1.

The Old Order. The title of this chapter refers to a system existing prior to Latour's appointment

as Bishop, when the Church of New Mexico was run by powerful local priests who also exercised political control°Xmen who felt few restraints from any higher religious or civic authority."Tyranny" is a word Cather frequently associates with this old order, which would thus include the legendary tyrant Fray Baltazar as well. Latour repeatedly associates Martinez with a period of tyranny that is drawing to a close (32, 141, 153). As a perception of a general historical trend, this is certainly true, but the association of tyranny specifically with the historical Antonio Jose Martinez is crude and unfair. Like Kit Carson, Martinez is a fictional character whose name Cather takes directly from history. In vilifying Martinez as an instigator of revolt who profited from the execution of his Indian parishioners, Cather is following the lead of histories she read°Xaccounts that have since been challenged by historians who strongly maintain Martinez's innocence. However, Cather is accurate in portraying Martinez as the powerful and charismatic leader of Mexican and Indian Catholics whose faith is strong but not particularly devoted to the standards of Santa Fe or Rome. The"Penitentes" (147), for example, were a Hispanic brotherhood who practiced prayer and bodily penance in imitation of Christ's suffering, and even reenacted the Crucifixion. Latour's challenge is to bring these Catholics under his authority without suppressing their religious spirit. For this reason, Latour decides to let Martinez remain in power until he can find a replacement whom the people will respect. Despite Martinez 's disobedience, Latour himself does have a certain respect for him:"Rightly guided, the Bishop reflected, this Mexican might have been a great man" (150).

2.

The Miser. Like Martinez, Father Marino Lucero is an actual historical figure whom Cather

alters and exaggerates for dramatic effect. Both represent the old order: the two"had not one trait in common... except the love of authority" (160). If Martinez is portrayed (unjustly, say recent historians) as lustful and sexually promiscuous, Lucero is driven by avarice:"He had the lust for money as Martinez had for women" (161). Together these two form a schismatic (rebellious) church opposing Latour's appointment of Father Talidrad to replace Martinez at Taos. Martinez dies in schism, but in Cather's fictionalized account, Lucero reconciles with the Catholic Church, in the person of Father Vaillant, on his deathbed. Lucero struggles with avarice until the end. It becomes clear that Cather is influenced by the traditional Christian conception of Seven Deadly Sins: anger, avarice, envy, gluttony, lust, vanity, and sloth. If Martinez is associated with lust and Lucero with avarice, what characters in the novel (before or after this chapter) are associated with these other sins?

| Top |

Book Six. Dona Isabella

1.

Don Antonio. Don Antonia Olivares figures most significantly as the main financial backer of

the cathedral that Latour hopes to build in Santa Fe. The cathedral is perhaps the novel's central image°Xprecious to Latour as"a continuation of himself and his purpose, a physical body full of his aspirations after he had passed from the scene" (175). Olivares announces his donation to the cathedral at a party he hosts with his wife Dona Isabella, an elegant woman, younger than Olivares, who enjoys singing for him. Latour reflects that each of the men at the party"not only had a story, but seemed to have become his story" (182). Latour's observation suggests that people's experiences shape who they become, an idea that Cather applied to physical things as well: Southwestern churches, she said,"are their own story." In like manner, Latour wants to embody his own story in his cathedral. To back up Latour's idea of people becoming their stories, Cather singles out one man at the party, Don Manuel Chavez, and tells a violent story from his past: his narrow escape from death while"hunting Navajos."

2.

The Lady. Following Olivares's death, his legacy to his wife and daughter is challenged by his

brothers, who claim that Dona Isabella is not old enough to be Inez Olivares's mother. In order to carry out Olivares's will, Isabella, who passes for being in her early forties, must testify in court that she is at least 52 years old. However, her vanity (one of the Seven Deadly Sins!) makes her reluctant to do so. Vaillant pressures, and Latour successfully persuades, Isabella to make the testimony. What is at stake is not only the financial security of Isabella and Inez, but Olivares's legacy to the Church as well, including his donation to the cathedral.

| Top |

Book Seven. The Great Diocese

1.

The Month of Mary. With the Gadsden Purchase, the United States °Xand with itn Latour's

diocese°Xexpands vastly, and Father Vaillant is eager to serve as a missionary in these territories long neglected by the Church. However, for the moment he is recovering from illness in Latour's garden, and Latour has a"cherished plan" to keep Vaillant with him in Santa Fe (208). This chapter unfolds, then, as a conflict between Latour's heartfelt desire for Vaillant's companionship, and Vaillant's heartfelt desire to serve the Mexican people he sees as his own. The time is May°Xthe month devoted in the Church calendar to Mary, Jesus' mother°Xand Vaillant remembers the decisive May day, years ago in France, when Father Latour supported him in his terrible struggle to leave his family and become a missionary in America (a moment to which Cather will return several times). Now Vaillant seems to feel no ambivalence in his departure; the struggle is all within Latour, who breaks a spray of tamarisk flowers"to punctuate and seal" the"renunciation" of his wish to keep Vaillant for himself (208). Suddenly Magdalena (the woman rescued from the murderer Buck Scales) appears amid a flutter of doves. How does the description of Magdalena 's entrance and of the birds' flight reflect upon the events in this chapter?

2.

December Night. Fighting a period of"coldness and doubt" after Vaillant's departure for

Arizona, a sleepless Latour rises one snowy December night to go to the church. He meets an old Mexican woman named Sada, who is being kept as a slave by an American Protestant family (at a time, just before the Civil War, when black slavery was legal, although for Sada, a Mexican, they have no legal title). Latour's spiritual drought is overcome by Sada's simple faith, which flows freely as she enters a church for the first time in nineteen years. In a remarkable reversal, the"church was Sada's house, and he was a servant in it." This chapter continues the theme of Mary introduced in the previous chapter. Mary represents"the Fountain of all Pity,""the pity that no man born of woman could ever utterly cut himself off from" (217). Latour feels the power of this pity as strongly as Sada does; he sees"through her eyes" (217).

3.

Spring in the Navajo Country. Breaking from travels in Arizona, Latour pays a visit to his

Navajo friend Eusabio, whose only son recently died. Needing time to"get his thoughts together," the Bishop spends three days alone in a hogan in Eusabio's settlement, as a sandstorm rages outside. Latour is still troubled by Vaillant's absence. The Bishop's reflections and memories portray Vaillant as a necessary complement to Latour's personality: although less distinguished in intellect and appearance, Vaillant has the stronger faith, a faith that drives him to accept hardship, learn languages, and embrace the imperfections of people much more readily than Latour, who is"cooler,""more critical," and"often a little grey in mood" (225).

4.

Eusabio. The upshot of the Bishop's reflections is to recall his vicar to Santa Fe. Dispatching

Jacinto to Tucson with the letter for Vaillant, Latour returns to Santa Fe with Eusabio as guide. This journey of nearly four-hundred miles gives Latour the opportunity to observe the character of the landscape in this part of the world, especially the overwhelming, active quality of the sky:"Elsewhere the sky is the roof of the world; but here the earth was the floor of the sky." He also watches how Eusabio interacts with the landscape:"Travelling with Eusabio was like travelling with the landscape made human" (232). Eusabio represents the Indian manner in general:"to vanish into the landscape, not to stand out against it" (233). Here Cather is developing a line of thought initiated in Book Three, when Latour observed near Acoma a diffuse"country... still waiting to be made into a landscape" (95), an incompletion he associated with the Acoma Indians themselves. That reading of the landscape implies what Latour recognizes here as"the European's desire to °•master' nature, to arrange and re-create." In these more mature reflections, the Bishop now appreciates in the Indian attitude an"inherited caution and respect" for the land (233).

| Top |

Book Eight. Gold Under Pike's Peak

1.

Cathedral. Two weeks after Vaillant's return to Santa Fe, the Bishop brings him to see the

yellow stone he plans to use for his new Cathedral. He reveals his plans for the building: it will be French Midi-Romanesque, like the Clermont Cathedral he knows from his youth. Latour thinks this style is"right" for New Mexico ; indeed, the stone reminds him of French stone (239-40). He sees the Cathedral as"not for us" but"for the future"; nevertheless, it is"dear to his heart" and even a matter of"vanity" for him (242). For his part, Vaillant, whose heart is with his Arizona flock, doesn't care what style the Cathedral takes.

2.

A Letter from Leavenworth. The letter from the Bishop of Leavenworth, Kansas, asks Latour to

send a priest to the newly booming gold mining region in Colorado, which now falls within the great diocese of Santa Fe. Vaillant is the obvious choice, and he accepts the challenge, because"it was the discipline of his life to break ties" and"move into the unknown" (246). The chapter ends with the Vaillant's memory of a young man from Chimayo, condemned to death for a crime of passion, who stitched a pair of boots for the statue of Santiago (also known as San Diego or Saint James). The boots of Santiago honor the travels of missionaries like Vaillant.

3.

Auspice Maria! After a month of preparations, during which he is outfitted with a special

wagon, Vaillant is ready to depart. Vaillant's simple faith shows itself in his remark to Latour that"the hands of Providence" caused the Bishop to recall Vaillant from Tucson so he could undertake the new mission to Colorado (250). Latour's confession that he recalled Vaillant selfishly for personal companionship suddenly exposes the Bishop's loneliness to his vicar. Note the deep feeling implicit in Latour's decision to give Vaillant both Contento and Angelica, because these old mules"have worked long together" and shouldn't be separated (252). After Vaillant's departure, Latour feels the presence of Mary;"with the help of Mary" ( Auspice Maria ) he can move forward with his life. Father Vaillant's mission centers around his wagon, which carries him through all the Colorado mining towns and signifies his faith to move into the unknown. Vaillant's mobile wagon (whose parts are constantly breaking and being replaced) contrasts with Latour's stable Cathedral, which becomes a kind of substitute support for Latour in Vaillant's absence (see 268-69). If Vaillant's motto, revealed in Book One, is"rest in action" (36), Latour's might be expressed as the reverse:"action in rest." Occasionally Vaillant returns to Santa Fe to beg support for his Colorado missions from the generous Mexican people, who ironically, have more to give than the wealthier Colorado miners. On one such visit, Latour calls Vaillant"a better man than I" and asks his blessing (259).

| Top |

Book Nine. Death Comes for the Archbishop

1.

Latour retires to a small adobe house with a chapel four miles outside Santa Fe. He tends his

garden and trains the young French priests, one of whom°XBernard Ducrot°Xbecomes"like a son to Father Latour." The Bishop's claim that"God himself has sent me this young man to help me through the last years" smacks of Vaillant's simple belief in miracles (265-66). Latour has grown closer in spirit to Vaillant, who is now dead. The Bishop tells Vaillant's sister in a letter:" I feel nearer to him than before. For many years Duty separated us, but death has brought us together" (263).

2.

The ailing Bishop tells Bernard,"Je voudrais mourir a Santa Fe" ("I would like to die in Santa

Fe"), and arrangements are made for his return. Making his last entry into the city late one February afternoon (the same time of day when he first saw Santa Fe ; see 21-22), Latour contemplates"the open, golden face of his Cathedral." He admires two aspects of its appearance: its suggestion"of the South" (that is, the south of France ), and its dramatic, almost operatic relationship with the hills behind it. These"steep carnelian hills" are part of the

Sangre de Cristo ("blood of Christ") mountains. Latour is

pleased to have built a Cathedral that fits into its surroundings. As his young architect Molny used to say,"Either a building is a part of a place, or it is not. Once that kinship is there, time will only make it stronger" (270). Compare and contrast this description of the Cathedral to that of the church at Acoma (100-101). Why does the Bishop consider his Cathedral successful but the Acoma church unsuccessful? Does his Cathedral follow the"Indian manner to vanish into the landscape, not to stand out against it" (233)?

| The Santa Fe Cathedral, at sunset, with the Sangre de Cristo Mountains in the background. Photograph Copyright 2005 by Joseph C. Murphy |

pleased to have built a Cathedral that fits into its surroundings. As his young architect Molny used to say,"Either a building is a part of a place, or it is not. Once that kinship is there, time will only make it stronger" (270). Compare and contrast this description of the Cathedral to that of the church at Acoma (100-101). Why does the Bishop consider his Cathedral successful but the Acoma church unsuccessful? Does his Cathedral follow the"Indian manner to vanish into the landscape, not to stand out against it" (233)?

3.

The Bishop chose to spend his final years exiled in New Mexico, rather than in the

sophisticated, historical surroundings of his native Clermont, because there is a quality in the morning air of New Mexico that makes him feel young and free.

4.

One of the Bishop's morning activities is to dictate"facts" (actually both"truths and

fancies") about the old missions (274). These facts serve as a reminder that the French missionary effort he has supervised is not the first one in this part of the world. He was preceded by the Spanish Fathers, who faced a landscape and culture even more alien to European sensibilities and beliefs than the one Latour inherited. Latour arrived in a New Mexico already cultivated by two centuries of Christian culture. The stories of these early missionaries is one part of this culture. One of Latour's favorites is about Father Junipero Serra being hosted by the Holy Family in the desert.

5.

In the afternoons the Bishop looks back over the times he shared with Joseph Vaillant,

especially the beginning of their journeys, when the two young priests first pledged themselves to the American missions. They decided to leave without parental permission, but Vaillant's resolve was shaken by the prospect of disappointing his passionate widower father."[T]orn in two by conflicting desires," Vaillant receives crucial support from his friend Latour as the diligence (stagecoach) approaches to take them to Paris (283). The image of the approaching diligence is a recurring one in the text, underscoring the importance of this moment for the two men: see 204 and 297. Latour's support comes in the form of the practical, incremental perspective that often shapes his decision-making as a Bishop: first, leave for Paris, then seek the father's consent. What similarity can we see between Latour's advice to Vaillant back then and his way of dealing with problems as Bishop, for example, the tyrannical Martinez or Sada's abusive keepers?

6.

In has last days Latour's consciousness focuses on the Past rather than on death. He perceives

that life is only an experience of the Ego (the self)°Xthat the self is not the same as one's life, is not limited by the accidents of one's life. His memories lose their order in"calendared time" and exist"all within reach of his hand, and all comprehensible" (288). What other perspectives on time are raised by Eusabio's visit, by train, at the end of this section?

7.

Eusabio's visit introduces the issue of the Navajos, who were forced by the U.S. government

to leave their ancestral country during Latour's tenure as bishop. The Bishop's"own misguided friend, Kit Carson," was the military officer charged with carrying out this brutal policy. This digression into American Indian affairs so close to the end of the novel has at least two purposes. First, it demonstrates Latour's pragmatic view of history. When the Navajo chief Manuelito begs Latour to appeal to the U.S. government on his people's behalf, Latour replies that as a Catholic priest in a Protestant country, he cannot"interfere in matters of Government" (294). Eventually, the Navajo are restored to their homeland, and Latour is thankful to see the"happy issue" of this wrong, as well as the wrong of black slavery:"I have lived to see two great wrongs righted," he tells Bernard (290). The Bishop's responses to these historical events are open to question. Was Latour right to deny Manuelito's request to appeal to the government, or did Latour have a moral responsibility to do so? And is Latour correct to say that the wrongs done to the Navajos and to black slaves have been"righted," after so much suffering and death, and at a time when African-Americans, although free, still lacked basic civil rights?

A second purpose of this Navajo section is to characterize once more the vast difference between the traditional Indian and white European conceptions of the landscape. For the Navajos, places like Canyon de Chelly are inseparable from their religion°X"More sacred than any place to the white man" (293). Whereas the Navajos require a specific place to practice their beliefs, Latour's life has been a study in transplanting culture and belief from place to place. Cultural mobility and adaptation seem to be defining features of European civilization.

A second purpose of this Navajo section is to characterize once more the vast difference between the traditional Indian and white European conceptions of the landscape. For the Navajos, places like Canyon de Chelly are inseparable from their religion°X"More sacred than any place to the white man" (293). Whereas the Navajos require a specific place to practice their beliefs, Latour's life has been a study in transplanting culture and belief from place to place. Cultural mobility and adaptation seem to be defining features of European civilization.

8.

In his final hours, as people of all races gather about the Cathedral, the Bishop seems to

sleep. His last thoughts, however, take him back to that passage in his youth when he helped Vaillant manage his indecision about becoming a missionary. In that moment, when"the time was short, for the diligence for Paris was already rumbling down the mountain gorge," Latour helped Vaillant find the"Will" necessary to move forward (297). Why is this moment so crucial in the novel? What does it say about the kind of man Latour is, and the kind of man Vaillant is°Xand the kind of man each will become?

The morning after his death,"the old Archbishop lay before the high altar in the church he had built" (297). In death, the Archbishop becomes one with his Cathedral. Why is this a fitting end to the novel?

The morning after his death,"the old Archbishop lay before the high altar in the church he had built" (297). In death, the Archbishop becomes one with his Cathedral. Why is this a fitting end to the novel?

| Top |