Behind the Singer Tower

Joseph C. Murphy

Text: Willa Cather's Collected Short Fiction. Ed. Virginia Faulkner and Mildred R. Bennett. Lincoln, NE: U of Nebraska P, 1970. 43-54.

Outline

I. Introduction

II. Structure

III. The Fire

IV. The Foundation

V. Significance of Title

Published in 1912, when Cather was working in New York for McClure's magazine, "Behind the Singer Tower" addresses questions that are still relevant a hundred years later: Why do we build taller and taller skyscrapers? Do the excitement, spectacle, and ideals associated with tall buildings justify their hidden costs and risks? Although the 35-story Mont Blanc Hotel, the story's focus, would be dwarfed by the Taipei 101 of today, it provides no less cause for reflection on the meaning of urban life. Cather's concern with such urban problems shows her in a phase of "muckraking"¡Xthat is, exposing social problems and injustices through writing. Still, like "Paul's Case," this story is a work of art that attains a complex synthesis of realism and idealism.

The story is narrated by a journalist who¡Xalong with Johnson (also a journalist), the engineer Fred Hallet and his draftsman, a lawyer, and the Jewish doctor Zablowski¡Xare on a boat ("launch") off the island of Manhattan. It is nighttime, and these men are talking about the disaster of the previous night: the burning of the Mount Blanc Hotel, which has resulted in the deaths of over 300 people. While the "framing" narrator reflects upon the Mont Blanc fire, Fred Hallet, the internal narrator, tells the story of an earlier, unnoticed disaster that occurred when the Mont Blanc was being built. This structure shows the probable influence of Joseph Conrad's 1902 novel Heart of Darkness, in which a framing and an internalnarrator are also assembled with a group of male listeners on a boat off shore of a great city (London).

According to the framing narrator, the fire in the Mont Blanc seems to challenge "the New York idea" of tall buildings:

Those incredible towers of stone and steel seemed, in the mist, to be grouped confusedly together, as if they were confronting each other with a question. They looked positively lonely, like the great trees left after a forest is cut away. One might fancy that the city was protesting, was asserting its helplessness, its irresponsibility for its physical conformation, for the direction it had taken. (44)

Certainly the most chilling detail the narrator mentions about the fire is that of "a man's hand snapped off at the wrist" discovered on the fifteenth-floor window ledge (45). The hand belonged to the famous Italian tenor Graziani, who had jumped from the thirty-second floor. This grotesque image represents generally the fragmenting of human lives caused by the fire¡Xlives of mostly wealthy and famous people like Graziani.

The internal narrator Fred Hallet shifts attention from the fire in the hotel's tower to something that happened when the building's foundation was being dug. Hallet was foreman of a crew of immigrant laborers digging the enormous hole. His story concerns his friendship with one of these men, an Italian immigrant named Caesarino, and his rivalry with the project manager, the ambitious and unethical engineer Stanley Merryweather, who believes that "men are cheaper than machinery" (51). Caesarino is crushed to death, along with numerous coworkers, by a piece of machinery dropped from the weak cabling that Merryweather refused to replace. Caesarino, an anonymous immigrant, is a foil for the famous Italian Graziani: the building takes both their lives, but only Graziani appears in the newspapers. As Hallet observes: "There's a lot of waste about building a city. Usually the destruction all goes on in the cellar; it's only when it hits high . . . that it sets us thinking" (53).

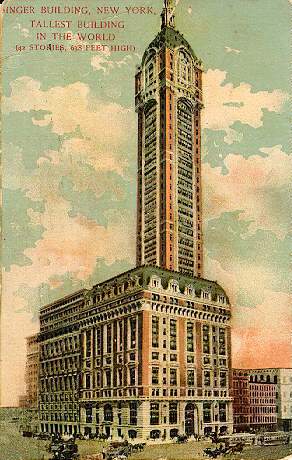

The title "Behind the Singer Tower" is a bit misleading because the Singer Tower is not the story's main concern. The Singer Tower was an actual skyscraper standing 612 feet (187 meters) tall, completed 1908 and demolished in 1968. It was the tallest building in the world in 1908-09. In the story it is discussed as having a particularly foreign look¡XJewish, or Persian, or Asian. It seems to represent the alien quality of tall buildings in general¡Xand the suspicion that they are infecting American life, even as they attract foreign laborers to build them. At the end of the story, Hallet mentions "a new idea of some sort" that will arise from all these new buildings, an idea that the Singer Tower itself will someday bow down to worship (54). This emerging idea is what the engineer Hallet thinks is "behind" the Singer Tower, the Mont Blanc Hotel, and other such urban constructions. But there are questions that linger after Hallet's narration: What is this idea? Is it worth the cost? Along with these questions lingers the more poignant question in Italian that Hallet remembers as Caesarino's last words: "ma, perche?" ("But, why?"). Does Hallet answer this question?

|

|

The Singer Tower. Picture from http://www.nyc-architecture.com/GON/GON003.htm |

|