The

Seventeenth Century

American Literature--

The Puritans

Provider:

Dr. Margarette

Connor & Dr.

Ron Tranquilla

|

Concept & Background in the ColonialPeriod of American Literature Concept

1: Discover America The Puritans John Calvin's Five Points Calvin (1509-1564) was a Protestant reformer in Geneva, Switzerland whose theological beliefs he summarized in "five points" which became the basis of the Presbyterian church and formed the basic theological tenets of Puritan theology. Calvin's points, based on a literal interpretation of the first chapters of Genesis, are: Total Depravity--Human beings are totally evil, born sinners because of Adam and Eve's sin of disobeying God in the Garden of Eden; God is all, hmans nothing and the source of all evil in the world. Unconditional Election--Although not obligated to do so, God has chosen to save ("elect") certain people, with NO reference to their lives or works; in fact, he knows beforehand who will be elect (predestination). Limited Atonement--Christ did not die for all, but only for the Elect. Irresistible Grace--God's grace is freely given by Him (to the Elect) and can neither be earned nor refused. Grace is God's saving power to redeem and save us through the forgiveness of sins, newness of life, the power to resist temptation, and peace of mind and heart. Perserverance of the Saints--God gives the Elect the full power to do God's will and live uprightly to the end of their lives. [TOP] --from Rod Horton and Herbert Edwards, Backgrounds of American Literature. Both Puritans and Dissenters believed in a "God of History," like the God of the Israelites, who would intervene actively and constantly in their lives. Both,

therefore, believed in a "Covenant Theology," believing that

each individual and each congregation must enter into a two-way covenant

with God , based on the Old Testament theme of covenant (c.f. Exodus'

Ark of the Covenant), as a way to explain the Calvinist doctrines of

Election and Perserverance of the Saints and God's relationship with

His creation. Both Puritans and Dissenters were "Calvinist."

The doctrine of Limited Atonement, that Christ did not die for all humanity

but only for the Elect, and that God has "elected" to save

these few, which election is foreknown (because God is all-knowing)

and foreordained and therefore not based on one's life or "goodness"

(because, since Adam and Eve's Fall, no humans are Good), is based on

Calvin's interpretation of many Biblical passages, for example, this

one from the book of Romans, 8:29-30: "29. For those whom he [God]

foreknew he also predestined to be conformed to the image of his Son,

in order that he might be first-born among many brethren. 30. And those

whom he predestined he also called; and those whom he called h e also

justified; and those whom he justified he also glorified." (Notice

how verse 29 relates to Calvin's doctrines of Unconditional Election

and Limited Atonement, and how verse 30 relates to Calvin's doctrines

of Irresistible Grace and Perserverance o f the Saints.) Early

American Women Writers: Voices in the Wilderness Life was seen as a test; failure led to eternal damnation and hellfire, and success to heavenly bliss. This world was an arena of constant battle between the forces of God and the forces of Satan, a formidable enemy with many disguises. Scholars have long pointed out the link between Puritanism and capitalism: Both rest on ambition, hard work, and an intense striving for success. Although individual Puritans could not know, in strict theological terms, whether they were "saved" and among the elect who would go to heaven, Puritans tended to feel that earthly success was a sign of election. Wealth and status were sought not only for themselves, but as welcome reassurances of spiritual health and promises of eternal life. The manifestation of this belief is one of the first big differences in American writing. Moreover, the concept

of stewardship encouraged success. The Puritans interpreted all things

and events as symbols with deeper spiritual meanings, and felt that

in advancing their own profit and their community's well-being, they

were also furthering God's plans. They did not draw lines of distinction

between the secular and religious spheres: All of life was an expression

of the divine will -- a belief that later resurfaces in Transcendentalism

and authors like Margaret Fuller and Louisa May Alcott From a lecture given by

Margarette Connor, 21 September 2000 at the American Library of Geneva

[TOP]

Thomas

Shepard: Preface to Peter

Bulkeley's Sermons (1651) Oh!

the depth of God's grace herein: that when sinful man deservres never

to have the least good word from Him, that He should open His whole

heart and p urpose to him in a Covenant; that when he deserves nothing

else but separation from God, and to be driven up and down the world

as a vagabond, or as dried leaves fallen from our God, that yet the

Almighty God cannot be content with it, but must make Himself to us,

and us to Himself, more sure and near than ever before! And is not

this Covenant then (Christian reader) worth thy looking into and searching

after? Surely never was there a time wherein the Lord calles to His

people to more serious searching into the nature of the Covenant than

in these days. . . . [TOP]

Journal [October 21, 1636] One Mrs Hutchinson [Anne Hutchinson, 1591-1643, a dissenter in the Massachusetts Bay Colony], a member of the church of Boston, a woman of ready wit and bold spirit, brought over with her two dangerous errors: 1. That the person o f the Holy Spirit dwells in [in fact, is in personal unity with] a justified person [one of God\rquote s Elect]. 2. That no sanctification can help to evidence to us our justification. . . . [October 25, 1636] The other ministers in the bay, hearing of these things, came to Boston at the time of the general court, and entered in private with them, to the end they might know the certainty of these things; that if need were, they might wr ite the church in Boston about them, to prevent (if it were possible) the dangers, which seemed hereby to hang over that and the rest of the churches. . . . [November 1, 1637] The court . . . sent for Mrs. Hutchinson and charged her with divers matters, as her keeping two public lectures every week in her house. . . and for reproaching most of the ministers. . . for not preaching a covenant of free grace. . . . [She claimed to the court that God had revealed to her that she would come into New England and be persecuted, and God would ruin the Puritans there for that reason]. So the court proceeded and banished her. . . . [March 22, 1638] . . .After she was excommunicated, her spirits, which seemed before to be somewhat dejected, revived again, and she glorified in her sufferings, saying, that it was the greatest happiness next to Christ, that ever befell her. . . . [Roger Williams, another significant banished and excommunicated dissenter, helped Hutchinson settle near Providence, R.I., Williams' colony, outside Massachusetts Bay Colony.] [TOP] "In Memory of my Dear Grandchild Anne Bradstreet Who Deceased June 20, 1669, Being Three Years and Seven Months Old" [Three of Bradstreet's grandchildren died as infants, Anne being the second] With troubled heart and trembling hand I write, The heavens have changed my sorrow to delight. How oft with disappointment have I met, When on fading things my hopes have set. Experience might 'fore this have made me wise, To value things according to their price. Was ever stable joy yet found below? Or perfect bliss without a mixture of woe? I knew she was but as a withering flower, That's here today, perhaps gone in an hour; Like as a bubble, or the brittle glass, Or like a shadow turning as it was. More fool then I to look on what was lent As if mine own, when thus impermanent. Farewell dear child, thou ne'er shall come to me, But yet a while, and I shall go to thee; Mean time my throbbing heart's cheered up with this: Thou with my Savior art in endless bliss [TOP] Diary Monday, April 29, 1695. The morning is very warm and Sunshiny; in the Afternoon there is Thunder and Lightening, and about 2 p.m. a very extraordinary Storm of Hail, so that the ground was made white with it, as with the blossoms when fallen; 'twas as big as pistoll and Musquet Bullets; It broke of the Glass of the new House about 480 Quarells [squares] of the Front; of Mr. Sergeant's about as much. . . . Many Hail-Stones broke throw the Glass and flew to the middle of the Room, or farther: People afterward Gazed upon the House to see its Ruins. I got Mr. Mather [the Reverend Cotton Mather, Sewall's pastor, who was visiting for dinner at the time] to pray with us after this awfull Providence; He told God He had broken the brittle part of our house, and prayd that we might be ready for the time when our Clay-Tabernacles [our bodies] should be broken. . . . [TOP] --by Charles Downey, Los Angeles Times Syndicate [The first Thanksgiving was not held in November, and the meal probably included no Turkey. If you wanted to recreate the first Thanksgiving. . .] . . . To be true to the occasion, you would hold the feast in late September or early October. Then, you would eat and make merry for at least three days. . . . You would not call the holiday Thanksgiving but a "harvest home" festival. To really drive home the point, call yourself a "Saint," not a Puritan, dress up in some colorful clothes, put on a feathered cap. . . . Then, dig into a second helping of eel. . . . The harvest home festival started in the Middle Ages and was held when a good crop was brought in. . . . Whenever it was held, the occasion was marked by food and merry-making. To the first English settlers to America, the word "thanksgiving" did not denote a holiday but a day spent in church praying. The myth of the black-and-white garbed Puritan arose because most people of the time were pictured in black--their Sunday finery--when they had their portraits painted. Black was a very expensive dye in the 1620s and quickly faded to purple, making the garb the most expensive. The easiest dyes, all takeb from vegetables, were red, yellow, and green. The first English settlers actually were a colorful lot who wore multi-hued capes, velvet vests with brass buttons, lace and quilted caps and soft boots [of suede]. . . . Inventories from the period show that church leaders even wore green and red underwear. . . . . . . Our Puritan forefathers from England actually were essentially lusty Elizabethans who valued wit and humor and knew how to have fun. A weekly duty for every housewife was the making of beer. Hard cider and a liquor that tasted like brandy were also available. The "Saints" drank alcohol because they considered drinking water to be bad for their health. . . [The "Saints" ate few turkeys, but lots of eels.] Cranberries aren't mentioned in the records at Plimouth until 1650. Probably because it required too much sugar to make the bitter berries tasty. Turkeys became associated with Thanksgiving when Abraham Lincoln made the holiday a national one in 1863. The real treat for the English at the first Thanksgiving was venison. Local Indians, who outnumbered the English 90 to 50, contributed 5 deer to the feast. In England, deer belonged exclusively to royalty and it was against the law for a commoner to eat deer meat. The feast was rounded out by fowl like goose and duck, rabbit, fish, shellfish like clams, and lobster. The tables were also graced with sou ps, meat pies, skillet-fried bread made of corn, dried fruit, and all kinds of wild berries. Researchers claim the English settlers were not too fond of vegetables, but they did eat a lot of squash and pumpkin. The celebration included singing, dancing, shooting matches among the English with their heavy, clumbsy muskets, and with the Indians, who showed their marksmanship with arrows. One of the popular games of the day, stool ball, was probably the ancestor of today's cricket and perhaps baseball. One player threw the ball while another used a three-legged stool to hit the ball and run to the equivalent of 17th Century bases. They played tug o' war, and saber tossin' . . .--a log, often the size of a small telephone pole, would be thrown as far as possible. . . . [TOP]

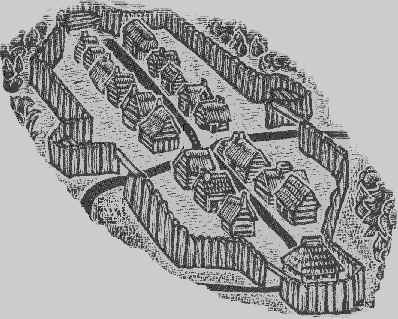

Plimouth Colony, 1627

Path through

the gate and village, Plimouth Colony, 1627

Field at the edge of Plimouth Colony

Saw-pit for cutting logs into planks

|