I. Life and Works

II. Fictional Method and Style

III. Modernism

IV. Cather and History

V. Willa Cather's America

The following biographical materials are available online at the Willa Cather Archive:

A chronology:

http://cather.unl.edu/life/chronology.html

A short biographical sketch (500 words):

http://cather.unl.edu/life/brief_bio.html

A longer biographical sketch (3000 words):

http://cather.unl.edu/life/longer_bio.html

A full-length biography: James Woodress, Willa Cather: A Literary Life. Lincoln: U of Nebraska P, 1987:

http://cather.unl.edu/life/woodress.html

Cather invokes the bare stage of ancient Greek theatre and the New Testament image of ˇ§that house into which the glory of Pentecost descendedˇ¨ as examples of the kind of suggestive simplicity she favored in fiction. By ˇ§not naming,ˇ¨ Cather was not rejecting realism completely, but seeking a greater truthfulness to how life is experienced, and to what is most durable in experience.

Cather's restrained method can be witnessed not only in her choice of words but in her choice of narrative structures. She was as exacting with plot as she was with language. She tended to reject sensational storylines in favor of unconventional or indirect presentations of experience. Her novel My Antonia (1916) is, she said, ˇ§just the other side of the rug, the pattern that is supposed not to count in a story. In it there is no love affair, no courtship, no marriage, no broken heart, no struggle for success. I knew I'd ruin my material if I put it in the usual fictional pattern. I just used it the way I thought absolutely true.ˇ¨ In Death Comes for the Archbishop (1927) she strove to write ˇ§something without accent, with none of the artificial elements of compositionˇ¨ˇXˇ§not to use an incident for all there is in itˇXbut to touch and pass on.ˇ¨ In both My Antonia and A Lost Lady (1923) she employs male characters as filters through which to study her heroines. In The Professor's House (1925), Cather inserts the first-person narrative of a young man, who died years before in the Great War, in order to illuminate the life of her title character. Her novels achieve unity not through strong plotline but through the cumulative power of incidents carefully selected and selectively viewed. Frequently, sensational or violent events are reported indirectly, in passing. Although less sensational than Faulkner's, Cather's novels often share with his a strategy of weaving together shorter narratives into a total structure.

![]() experimenting with narrative structures, temporal frameworks, narrative voices, and symbols;

experimenting with narrative structures, temporal frameworks, narrative voices, and symbols;

![]() exploring inner consciousness as a major theme;

exploring inner consciousness as a major theme;

![]() adapting the abstract methods of modern painting to literature;

adapting the abstract methods of modern painting to literature;

![]() embracing communities steeped in tradition and history (both Western and ˇ§primitiveˇ¨ traditions) as a relief from the upheavals and alienation of modernity.

embracing communities steeped in tradition and history (both Western and ˇ§primitiveˇ¨ traditions) as a relief from the upheavals and alienation of modernity.

- Three of her novels meet the conventional definition of historical fiction: they are fictional reconstructions of historically remote times and places. Death Comes for the Archbishop recreates the American Southwest of the nineteenth century, and Shadows on the Rock (1931) does much the same for seventeenth-century Quebec. Both are based partly on historical documents and integrate actual historical figures with fictional characters. In her final novel, Sapphira and the Slave Girl (1940), Cather looks back to the pre-Civil War slave culture of her native Virginia.

- Two other novelsˇX The Song of the Lark (1915) and The Professor's House (1925)ˇXincorporate history through modern characters' encounters with the archeological remnants of the cliff-dwelling Indians of the Southwest; moreover, Cather's professor in the latter novel, Godfrey St. Peter, is a historian of the Spanish exploration of the Americas.

- Much of Cather's fiction is historical insofar as her characters are preoccupied with history. Numerous characters survey their personal histories to make sense of their present lives. For Cather, childhood is the reservoir of the self, the site of what Jim Burden in My Antonia calls ˇ§those early accidents of fortune which predetermined for us all that we can ever be.ˇ¨ Other characters survey cultural history, within and beyond their own lifespans, as a touchstone for personal experience. This recourse to history is frequently intensified by a character's exile status. Archbishop Latour, for example, looks to his early days in France, and to the history of Catholicism in the Old and New worlds, to gain perspective on his ministry in New Mexico. Likewise, Alexandra Bergson and Antonia Shimerda gauge their American progress against their European memories. Many of Cather's characters are exiles trying to transplant their memories of an older culture into a newer American field. This is the classic American immigrant story. It is a story of both loss and gain: the vastness of the landscape and the diversity of the American population are consolations for the constraints these immigrants left behind. In contrast to Faulkner's characters, who are sometimes overburdened with historyˇXtheir families having lived in the same place for some generationsˇXCather's emigres struggle to keep hold of history.

| Farmland in Webster County , Nebraska , outside Red Cloud. Photograph by Joseph C. Murphy |

| The home of Annie and John Pavelka, Cather's prototypes for Antonia and Cusak in My Antonia and the Rosickys in ˇ§Neighbour Rosicky.ˇ¨ Photograph by Joseph C. Murphy |

Cather never lost her yearning for older civilizations, and she increasingly heeded their call. After graduating from the University of Nebraska, she worked as a magazine editor and high school teacher in the teeming industrial city of Pittsburgh, from 1896 to 1906, before joining McClure's magazine in New York. The vital arts culture that flowered alongside capitalism in American cities, especially Pittsburgh, New York, and Chicago, is one of Cather's concerns in ˇ§Paul's Caseˇ¨ and The Song of the Lark. Cather made a home in New York for the rest of her life. While she enjoyed the benefits of America 's cultural metropolis, she also used it as a base from which to explore places that meant more to her. Cather had first visited Europe in 1902, and she returned there repeatedly, with an increasing focus on France in the 1930s.

|

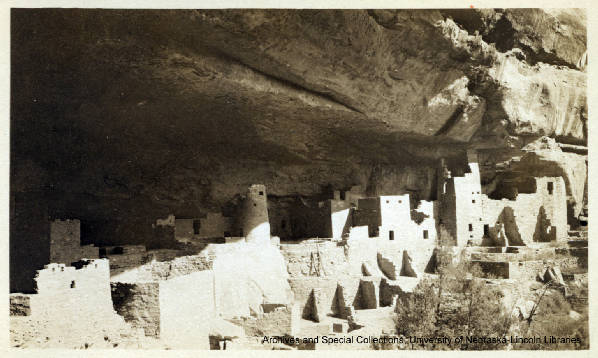

Mesa Verde, Colorado, around 1915. |

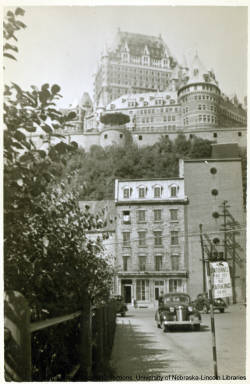

She first visited the American Southwest ( Colorado, Utah, New Mexico, and Arizona ) in 1912, and immediately recognized there an historical depth she found lacking in much of North America. Here European colonial and missionary contacts dated back to the 1500s, and the Anasazi Indians had built fine stone cities into cliff walls in pre-Colombian times. In The Song of the Lark and The Professors House, Cather's characters seek imaginative connections with these ancient Indians and with the Europeans who first explored the region. Death Comes for the Archbishop, focusing on two French Catholic missionaries in New Mexico, recreates the mesh of French, Spanish, Mexican, Indian, and Anglo cultures in the Southwest during the second half of the nineteenth century. In 1928 Cather visited Quebec City ( Canada ), which inspired her next novel, Shadows on the Rock, set in Quebec in the 1600s.

|

Chateau Frontenac, Quebec City, 1928. |

New Mexico and Quebec had a similar appeal for Cather: they were predominantly Catholic cultures with rich histories dating back hundreds of years. She found in them an alternative to American Puritan history, centered in New England and originating in England. Her alternative American history originated in France and Spain, and was ultimately oriented toward Rome. By opening up this history Cather brought cultural and geographical complexity to the American novel. She demonstrated the continuity of the United States with the historically Indian and French territory to the Northeast and historically Indian and Spanish territory to the Southwest.

Cather's final work adds to the geographical complexity of her accomplishment. Her last completed novel, Sapphira and the Slave Girl, is set in antebellum Virginia, some decades before she was born in that state. At the time of her death in 1947 she was working on another historical narrative, Hard Punishments, set in 1340 in Avignon, France.