莊士弘

July, 2010

Nomad 遊牧

「遊牧」一概念,乃是用來對抗「國家」(State ; Etat) 或「國家機器」(State apparatus ; l'appareil

d'Etat)的形成。遊牧民族逐水草而居;他們就是流浪者,隨著季節的嬗遞而流變。他們沒有一個固定的家。他們哪

裡都是他們的家,當然哪裡也都不是他們的家。這個概念,乃是為了鬆動(undo; defaire)那固定居所的農村式的生活—一種穩固、同質、無以改變的生活模式。所謂的「定居式生活」體現在農村式生活:人類文明從灌溉水利系

統的興建,乃至於一個固定主體性的國家文明的建立。如此一來,農村式的生活也預示著它未來追求一個穩定、固定的定居式社會模式。這顯然是德勒茲與瓜達西(以下簡稱「德-瓜」)兩人所拒斥的概念。

根據Antonioli的說法,德勒茲早在《差異與重覆》一書批判了以往以概括化或同一化傾向的思想。她說:

Ce qui est en jeu est donc une

orientation generale de la philosophie, un tropisme fundamental qui

l'attire irresistiblement vers le Meme et l'Identique. Tout en

affirmant vouloir se debarrasser des prejuges infondes et irreflechis

de la doxa, la philosophie choisit a son tour l'experience banale et

quotidienne de la Recognition, au lieu d'affronter des aventures plus

etranges et des voyages plus inquietants. (Antonioli 23)

What is thus concerned is a

general orientation of philosophy, a fundamental tropism that

irresistibly attracts it to Sameness and the Identity. Affirming the

will to get rid of the prejudices and the un-reflected doxa,

philosophy chooses in its own term the banal and everyday experience of

Recognition, instead of affronting any adventures and voyages, which

are more foreign and disquiet. (Antonioli 23;【我的英譯】)

如此一來,思想將成為無法反思的偏見、意見(doxa),並淪為認同意義下,百無聊賴的日常生活經驗。所以,德勒茲所疾呼的態度是,勇於面對全然域外世界的冒險或旅行。如此一來,一個個

體方能擺脫自我個體化,能與任何域外的(outside ;

dehors)他者或事物作連結,並自我流變為他者。如此的個體方才不會淪

為固步自封、剛愎自用,並且具排他性的態度。猶如一個旅人或遊牧者,他/她不會永遠蟄居同一個地方(像我們填任何報名表格

都要求一個「永久住址」);他/她離開,他/她旅行;他/她

對於任何域外都是敞開的,並且自身永遠與異質的元素做結合,以流變為自我陌生化,自我他者化的個體。

在往後的數十年,德勒茲與瓜達西所合著的《千重台》中的第十二章<論游牧學──戰爭機器>[1],

他們認為國家形式的政體──或「國家機器」──就如同一種內在化(interiority)的形式,不斷地以與自我形像相同的方式將任何異質或他者性(alterirty)納入進自我的主題裡頭。

The State-form, as a form of interiority,

has a tendency to reproduce itself, remaining identical to itself

across its variations and easily recognizable within the limits of its

poles, always seeking public recognition (there is no masked State).

(ATP 360)

《千重台》的第一章即明確指出,所謂的歷史,乃是一部遺忘遊牧者的歷史[2];它所強調的是一部文字的、統一的(unitary)歷史,係由定居式(sedentary)國家[3]或政體所書寫的。他們說:

[h]istory is always written from the

sedentary point of view and in the name of a unitary State apparatus,

at least a possible one, even when the topic is nomads. What is lacking

is a Nomadology, the opposite of a history. (ATP 23)

德-瓜迫逼讀者來正視:漫遊於邊界上,逐水草而居的遊牧民族,他們與土地的關係,並非所謂定居式的關

係;反之,應是「處處皆是家,但卻處處皆不是家」的遊牧式生活型態。他們的歷史乃由口傳,並非邏格斯(logos)中

心的文字書寫。所以,若以邏格斯中心的「歷史」來作考慮的話,他們是

“沒有” 歷史的,並在歷史的洪流中被淹没-消聲

-消逝。如此一來,德-瓜所謂的「遊牧學」便突顯出以邏格斯文字書寫的文字歷史,內蘊著政治、文化、文明以及歷史等等

的暴力。

在Robert

Sasso 與 Arnaud Villani所編纂的《德

勒茲詞彙》(Le

Vocabulaire de Gilles Deleuze)中,他們根據德勒茲的《差異與重覆》指出「遊

牧學」的特色:1)平滑空間與非條紋空間(如:沙漠);2) 作為去轄域化形式的逃逸路線;3)絕對的速度、無法測量,並可能與不可動性(immobilite/

immobility)有關;4)全然外在於國家的戰爭機器。(Sasso

and Villani 355)

其中,筆者認為最為顯著的特色是「戰爭機器」:

其全然外在於國家機器,並防止國家的形成。先前段落中,我們得知,德勒茲思想是深懼陷入同質化或同一化的窠臼之中;而國家,或

國家機器,則全然服膺並且體現德勒茲所拒斥的統一化或同一化。所以,遊牧學作為一種戰爭機器的姿態(gesture),

其目標不是它字面意義上的「戰爭」[4],而是防止國家同質性的形成。

如此,不禁使我們聯想起2003年諾貝爾得主的南非/澳洲作家,科慈(J. M. Coetzee)所著的《等待野蠻人》(Waiting for the

Barbarians)。[5]故事中,印入眼簾的,是帝國駐守在沙漠(這

是德勒茲明確指出的「平滑空間」),亦或是「土地的混雜力量」

(Grant186)。但是在這種混雜力量的沙漠上,卻建立著灌溉系統(這是德勒茲所指的「條紋空間」)。而對於游牧式生活的野,總是喜歡在深夜時的攻擊這些所謂定居模式的產

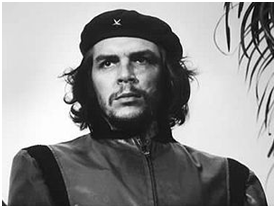

物──農業灌溉系統。這些野蠻人的目的不是要打勝戰,抑或使他人屈服,而是為了防止國家機器的灌溉系統的蔓延,並進而統御他們游牧的生活。他們就像打游擊戰的切•格瓦拉(Che

Guevara)(如下圖)、越戰中的

越軍、成吉斯汗[6]、畢拉登[7]等,以對抗有組織、有系統的軍

隊。

《Guerrillero Heroico》(西班牙語:英勇的游擊隊員)[8]

l

對

全球勞動遷移的啟發

在Michael

Hardt與Antonio Negri所合著的《帝國》(Empire)中,他們認為現代化(modernity)以降的帝國,對於全球勞動力市場做出的無情的控制,試圖加以捕追,並

且控制其勞動力的流動及遷移:

Throughout the history of modernity, the

mobility and migration of the labor force have disrupted the

disciplinary conditions to which workers are constrained. And power

has wielded the most extreme violence against this mobility. In

this respect slavery can be considered on a continuum with the various

wage labor regimes as the most extreme repressive apparatus to block

the mobility of the labor force. The history of black slavery in

the Americas

demonstrates both the vital need to control the mobility of labor and

the irrepressible desire to flee on the part of the slaves: from the

closed ships of the Middle Passage to the elaborate repressive

techniques employed against escaped slaves. Mobility and mass

worker nomadism always express a refusal and a research for liberation:

the search for freedom and new condition of life. (Hardt and Negri

212l; 中譯本248)

l

對現代公

民權的啟發:

對當代所謂的「公民權」(citizenship),Eugene W. Holland 則在他的<肯定式的遊牧學與戰爭機器>[9]一文中,提出「遊牧公民權」(nomad citizenship)的概念,以補充(supplement)或替代以往由國家或資本主義為主概念下的「公民權」。Holland認

為現代公民權的概念,乃是由一國家所制定且劃定的一條疆界、領域等。這樣的國家模式是封閉的,並具排他的條紋空間。因此,遊牧公民權意圖抹除、替代所謂國

家的疆界。遊牧公民權所連結的,不是國家所定義下或垂直式的公民權;反之,是水平式的結盟(engagement)。換言之,遊牧公民權係指直接水平式地與其他民族,其他的團體產生關係 (223-24) 。

抑有進者,Hardt與Negri在《帝國》(2000)提出「Papier pour tous!」(讓所有人都有証件!)以及「全球公民權」(global citizenship)的概念,試圖瓦解早期帝國對諸眾(the

multitude)的生產與生命的控制(400; 中

譯本455)。他們認為:

The general right to control its own

movement is the multitude's ultimate demand for global citizenship.

This demand is radical insofar as it challenges the fundamental

apparatus of imperial control over the production and life of the

multitude. Global citizenship is the multitude's power to

reappropriate control over space and thus to design the new cartography.

(英400; 中譯本455)

*

對

德-瓜的批判與反省:

耶魯大學法文系教授Christopher Miller[10]在其《國族主義者與遊牧者》[11]指出,Hubac[12]的著作比德-瓜兩人的《千重台》好讀多了,並且也寫的較清楚。再者,德-瓜兩人所認為的遊牧戰爭機器往往忽略了它其實是會展開殺戮的

殘忍行為。Hubac指出游牧戰爭機器是讚頌戰爭的;他們戰爭,是為想達成和平的狀態。德-瓜的遊牧戰爭機器一概念,則忽

略了它會使用暴力、殺戮等野蠻方式,以達成和平。要之,他們的思想也忽略了倫理的部分 (Miller 204-05) 。

德-瓜兩人對於人類學與再現思維有著極為強烈的批判。然而,對Miller來

說,德-瓜卻是在履行一種樹狀(arborescent)或人類學的再現,這反倒是他們在《千重台》所亟欲批判的。他們在《千重台》的第一章指出的塊莖思維,主要想批判長久以來西方哲學以一種人類中心、樹狀式的再現方式來詮釋事物。

然而,他們所引用關於遊牧民族的文獻,往往來自於人類學家所書寫的著作。根據Miller的算法,德-瓜使用了十三筆資料(178),

這些資料都是人種、人類學家以人類中心的方式來再現活生生的遊牧民族。如此一來,他們是自相矛盾的:一方面他們引用以

再現式,樹狀的資料來再現那些活生生的遊牧民族,然而另一方面,他們卻宣稱自己是反殖民、反再現、反人類學、反樹狀的思想。職是之故,

他們何嘗不是自己所批判的「偽多樣性」(

“pseudomultiplicities”)[13]嗎? (Miller 172-82)

Bibilography

Antonioli, Manola. Geophilosophie

de Deleuze et Guattari. Paris : L'Harmattan, 2003.

Deleuze, Gilles, and Felix Guattari. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia.

[1980]. Trans. Brian Massumi. Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P, 1987.

Hamilton, Grant. “Becoming-Nomad:

Territorialisation and Resistance in J.M. Coetzee's Waiting

for the Barbarians.” Deleuze and the Postcolonial.

Ed. Simone Bignall andd Paul Patton. Edinburgh : Edinburgh UP, 2010. 183-200.

Hardt, Michael and Antonio Negri. Empire. Cambridge,

MA: Harvard UP, 2000.

Holland, Eugene W. “Affirmative

Normadology and the War Machine.” Ed. Constantin V. Boundas. Gilles Deleuze: The Intensive Reduction. London:

Continuum, 2009. 218-25.

Mengue, Philippe. Deleuze

et la question de la demoncratie. Paris : l'Harmattan, 2003.

---. « Lignes de fuites et

devenirs dans la conception deleuzienne de la litterature » Stefan

Leclercq 30-83.

Miller, Christopher. Nationalists

and Nomads: Essays on Francophone African Literature and Culture. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1998.

Patton, Paul. “Conceptual Politics and the

War-Machine in Mille Plateaux.” SubStance.

44.45 (1984): 61-80.

---. Deleuze and the

Political. New York

: Routledge, 2000.

Reid, Julian. “Deleuze's War Machine:

Nomadism against the State.” Millennium: Journal of

International Studies 32.1 (2003): 57-85.

Sasso, Robert and Arnand Villani, eds. Le Vocabulaire de

Gilles Deleuze.

Nice : Centre de recherches d'histoire des idees, 2003.

廖炳惠編著。《關鍵詞200:文學與批評研究的通用詞匯編》。南京:江蘇教育出版社,2006。

程

黨根。《游牧思想與游牧政治試驗:德勒茲後現代哲學思想研究》。北京:中國社會科學出版社。

程黨根。<游牧>。《西方文論關鍵詞》。趙一凡等編。上海:外語教學與研究出版社,2006。785-95。

陳永國譯。《游牧思想:吉爾•德勒茲 & 費利克斯•瓜塔里讀本》。吉林:吉林人民出版社,2003。

Hardt, Michael and Antonio Negri。楊建國 & 范

一亭譯。《帝國》。南京:江蘇教育出版社,2002。

[1] 其中文譯文可見陳永國的譯文,收錄於《游牧思想:吉爾•德勒茲&費

利克斯•瓜塔里讀本》。吉林:吉林人民出版社,2003。

[2] 在德勒茲的Dialogues中,他也說過同

樣的話, “But history has never

begun to understand nomads, who have neither past nor future” (38).

[3] 所謂「定居式國家」,也就是要有一個「永久居住地址」,以便

於國家的控制、管理、乃至追補。

[4] “The aim of the nomad war machine is not war itself,

but the nonbattle, a guerrilla warfare.” (ATP 416;

emphasis original).

[5] 可參見 Grant Hamilton, “Becoming-Nomad:

Territorialisation and Resistance in J.M. Coetzee's Waiting

for the Barbarians,” Deleuze and the Postcolonial,

Eds. Simone Bignall and Paul Patton (Edinburgh : Edinburgh UP, 2010) 183-200.

[7] “Au contact de tel passages nous ne

pouvons que sourire (ou nous inquieter, si on devait les prendre au

serieux : au nom de ces conceptions et de l'apologie du «barbare

migrant», on doit applaudir au terrorisme d'Al Qaida, et s' ecrier sans

hesiter : «Vive Ben Laden»). En effet, le radicalisme

revolutionnaire deleuzien est si certain et sans failles qu'il ne peut

que se saborder politicquement lui-meme »

” (Mengue 87 ; emphasis original).

[8] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Guerrillero_Heroico

[9] Eugene

W. Holland, “Affirmative Normadology and the War Machine,” Gilles

Deleuze: The Intensive Reduction, Ed. Constantin V. Boundas

(London: Continuum, 2009) 218-225.

[10] 上述的Eugene

W. Holland曾對Christopher Miller這篇文章有精采的筆戰。有興趣的讀者可參閱:Eugene W. Holland, “Representation and

Misrepresentation in Postcolonial Literature and Theory,” Research

in African Literature 34.1(2003): 159-73. (Accessed by Project Muse)

[11] Christopher

Miller, Nationalists and Nomads: Essays on Francophone

African Literature and Culture (Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1998).

[12] Miller

/span> 之所以談及Hubac的

作品,乃因為德-瓜兩人該篇文章,有一大部分是引用Hubac的的著作。

[13] 這個詞是德瓜在</span>千重台>的首章中所批判樹狀及根的概念,說明儘管該事物多麼的多樣化,但一旦是以主體為中心為開始,該事物的多樣性是枉

然了。它不再是多樣,而是「偽多樣」。例如,在布偶戲中的線,那些線在德-瓜的眼裡都是塊莖式、多樣式的,但一旦那些線由單一的藝術家來操縱的話,就有違其多樣式(multiplicity)了(Deleuze and Guattari 8) 。其原文為:it is only when the multiple is effectively treated as a

substantive, "multiplicity," that it ceases to have any relation to the One as subject or object,

natural or spiritual reality, image and world. Multiplicities are

rhizomatic, and expose arborescent pseudomultiplicities for what they

are. . . . Puppet

strings, as a rhizome or multiplicity, are tied not to the supposed

will of an artist or puppeteer but to a multiplicity of nerve fibers,

which form another puppet in other dimensions connected to the first:

"Call the strings or rods that move the puppet the weave. It might be

objected that its

multiplicity resides

in the person of the actor, who projects it into the text. ((8)

TOP