|

|

|

|

| Willa Cather |

| ���ԡE�ͷ� |

| �Ϥ��ӷ��Ghttp://www.courses.fas.harvard.edu/~cather/catherpix.html |

| �D�n�����GNovel |

| ��ƴ��Ѫ̡GKate Liu/�B����;Joseph Murphy/����;Ray Schulte/���ùp |

| ����r���GIntroduction to Literature 1998;American Literature |

|

|

|

|

Willter Cather: An

Introduction

|

|

Joseph C.

Murphy

|

|

|

Life and Works Life and Works

Fictional Method and Style

Fictional Method and Style

Modernism

Modernism

Cather and History

Cather and History

Willa Cather's America

Willa Cather's America

|

| |

Life and

Works Life and

Works |

| |

|

|

The following biographical

materials are available online at the Willa Cather Archive:

https://cather.unl.edu/

|

| |

| |

| |

Fictional Method and

Style Fictional Method and

Style |

| |

| |

Cather stated her credo of fiction

most forcefully in her essay ¡��The Novel Demeuble¡¨ (1922), meaning

¡��The Unfurnished Novel.¡¨ The title refers to her idea that the best

fiction does not merely ¡��catalogue¡¨ the furniture of life¡Xphysical

things, processes, and sensations¡Xbut selects such details carefully

to ¡��present [the] scene by suggestion rather than enumeration.¡¨ She

praises novelists like Hawthorne and Tolstoy whose settings ¡��seem to

exist not so much in the author's mind, as in the emotional penumbra of

the characters themselves.¡¨ Cather argues that, paradoxically, by

saying less, writers can say more. They can create a sense of something

beyond words: |

| |

| |

|

Whatever is felt upon the page

without being specifically named there¡Xthat, one might say, is

created. It is the inexplicable presence of the thing not named, of the

overtone divined by the ear but not heard by it, the verbal mood, the

emotional aura of the fact or the thing or the deed, that gives high

quality to the novel or the drama, as well as to poetry itself. |

| |

| |

Cather invokes the bare stage of ancient Greek theatre

and the New Testament image of ¡��that house into which the glory of

Pentecost descended¡¨ as examples of the kind of suggestive simplicity

she favored in fiction. By ¡��not naming,¡¨ Cather was not rejecting

realism completely, but seeking a greater truthfulness to how life is

experienced, and to what is most durable in experience.

Cather's restrained method can be witnessed not only in

her choice of words but in her choice of narrative structures. She was

as exacting with plot as she was with language. She tended to reject

sensational storylines in favor of unconventional or indirect

presentations of experience. Her novel My Antonia (1916)

is, she said, ¡��just the other side of the rug, the pattern that is

supposed not to count in a story. In it there is no love affair, no

courtship, no marriage, no broken heart, no struggle for success. I

knew I'd ruin my material if I put it in the usual fictional pattern. I

just used it the way I thought absolutely true.¡¨ In Death

Comes for the Archbishop (1927) she strove to write

¡��something without accent, with none of the artificial elements of

composition¡¨¡X¡��not to use an incident for all there is in it¡Xbut to

touch and pass on.¡¨ In both My Antonia and A

Lost Lady (1923) she employs male characters as filters

through which to study her heroines. In The Professor's

House (1925), Cather inserts the first-person narrative of

a young man, who died years before in the Great War, in order to

illuminate the life of her title character. Her novels achieve unity

not through strong plotline but through the cumulative power of

incidents carefully selected and selectively viewed. Frequently,

sensational or violent events are reported indirectly, in passing.

Although less sensational than Faulkner's, Cather's novels often share

with his a strategy of weaving together shorter narratives into a total

structure.

Top

|

| |

| |

| |

Modernism Modernism |

| |

| |

Cather is sometimes not named

alongside major modernists like Joyce, Proust, Woolf, Faulkner, and

Hemingway¡Xpartly because she gets categorized as a Nebraska regional

writer, and partly because her fiction seems, on the surface, less

challenging, experimental, or disillusioned than we expect modernism to

be. But in fact, Cather was a contemporary of these writer and

developed a brand of modernism that was as sophisticated as theirs. The

American modernist poet Wallace Stevens once remarked of Cather: ¡��We

have nothing better than she is. She takes so much pain conceal her

sophistication that it is easy to miss her quality.¡¨ Other modernists

too, like Woolf, Faulkner, and Sinclair Lewis, read and admired

Cather's work. Like them, she sublimated the trauma of modern

experience into new literary forms. Like them, she found her own way

amidst the various aesthetic options at the turn of the century:

realism, naturalism, symbolism, impressionism. She sought a deeper

account of experience than was typical of realism or naturalism, but

she valued the attention of those movements to common people and social

realities. Impressionism and symbolism (which she absorbed through

painting as well as literature) both influenced her fictional method

(impressionistic descriptions of landscapes and cityscapes; and her

knack for iconic symbols: the plough framed by the setting sun in My

Antonia, the strong swift man in Alexandra's dream in O

Pioneers! [1913], the mysterious ¡��stone lips¡¨ cave in Archbishop

); however, she rejected the brands of those movements

tending toward decadence or art for art's sake. Cather's work

demonstrates a number of qualities often identified with modernist

literature: |

| |

| |

|

- experimenting with narrative structures,

temporal frameworks, narrative voices, and symbols;

- exploring inner consciousness as a major

theme;

- adapting the abstract methods of modern painting to

literature;

- embracing communities steeped in tradition and

history (both Western and "primitive" traditions) as a relief from the

upheavals and alienation of modernity.

Top

|

| |

| |

| |

Cather

and History Cather

and History |

| |

| |

Willa Cather can properly be

considered a historical novelist. She did not write adventure-packed

historical romances in the vein of Sir Walter Scott or James Fenimore

Cooper; rather, she moderated her romantic vision with a critical,

realist edge and with experimental modernist techniques. Her use of

history can be divided into three types: |

| |

| |

|

- Three of her novels meet the conventional definition

of historical fiction: they are fictional reconstructions of

historically remote times and places. Death Comes for the

Archbishop recreates the American Southwest of the

nineteenth century, and Shadows on the Rock (1931)

does much the same for seventeenth-century Quebec. Both are based

partly on historical documents and integrate actual historical figures

with fictional characters. In her final novel, Sapphira and

the Slave Girl (1940), Cather looks back to the pre-Civil

War slave culture of her native Virginia.

- Two other novels¡X The Song of the Lark (1915)

and The Professor's House (1925)¡Xincorporate

history through modern characters' encounters with the archeological

remnants of the cliff-dwelling Indians of the Southwest; moreover,

Cather's professor in the latter novel, Godfrey St. Peter, is a

historian of the Spanish exploration of the Americas.

- Much of Cather's fiction is historical insofar as her

characters are preoccupied with history. Numerous characters survey

their personal histories to make sense of their present lives. For

Cather, childhood is the reservoir of the self, the site of what Jim

Burden in My Antonia calls ¡��those early

accidents of fortune which predetermined for us all that we can ever

be.¡¨ Other characters survey cultural history, within and beyond their

own lifespans, as a touchstone for personal experience. This recourse

to history is frequently intensified by a character's exile status.

Archbishop Latour, for example, looks to his early days in France, and

to the history of Catholicism in the Old and New worlds, to gain

perspective on his ministry in New Mexico. Likewise, Alexandra Bergson

and Antonia Shimerda gauge their American progress against their

European memories. Many of Cather's characters are exiles trying to

transplant their memories of an older culture into a newer American

field. This is the classic American immigrant story. It is a story of

both loss and gain: the vastness of the landscape and the diversity of

the American population are consolations for the constraints these

immigrants left behind. In contrast to Faulkner's characters, who are

sometimes overburdened with history¡Xtheir families having lived in the

same place for some generations¡XCather's emigres struggle to keep hold

of history.

Top

|

| |

| |

| |

Willa

Cather's America Willa

Cather's America |

| |

| |

Cather's fiction and life ranged

across the American continent to an extraordinary degree. Born in the

Southern state of Virginia, in 1873, Cather moved with her family to

the open Midwestern tableland of Nebraska at age 10. This uprooting was

the central event of her childhood and, indeed, of her life. It defined

her abiding fictional concern with exile: the adventure of new

frontiers, and the attendant longing for what is left behind. She later

recalled this childhood displacement in an interview: ¡��I was little

and homesick and lonely.... So the country and I had it out together

and by the end of the first autumn the shaggy grass country had gripped

me with a passion that I have never been able to shake. It has been the

happiness and curse of my life.¡¨ Cather's experience became that of

her narrator Jim Burden in My Antonia, and his

response to the Nebraska landscape captures something of Cather's

ambivalence: ¡��There was nothing but land; not a country at all, but

the material out of which countries are made.¡¨ To participate in the

making of a new country was for Cather, as it was for her character

Jim, a heroic and stirring project. And to do so alongside fellow

migrants and immigrants from the East Coast, France, Germany,

Scandanavia, Bohemia, and Russia gave the experience a richer cultural

dimension. If these refugees from the East and Europe made prairie life

tolerable for Cather, they also reminded her of older, more

sophisticated civilizations against which American pioneering appeared,

at its worst, crass and materialistic. This tension between the ideals

and realities of the American frontier occupies a number of Cather

novels, including O Pioneers!, The

Song of the Lark, My Antonia, One

of Ours (1922), and A Lost Lady. The

town of Red Cloud, Nebraska, where her family eventually settled, was

the prototype of the small frontier towns she repeatedly depicted in

fiction.

|

|

|

|

Farmland

in Webster County , Nebraska , outside Red Cloud. Photograph by Joseph

C. Murphy

|

|

|

| The home of

Annie and John Pavelka, Cather's prototypes for Antonia and Cusak in My

Antonia and the Rosickys in "Neighbour Rosicky." Photograph

by Joseph C. Murphy |

|

| |

Cather never lost her yearning for older civilizations, and she

increasingly heeded their call. After graduating from the University of

Nebraska, she worked as a magazine editor and high school teacher in

the teeming industrial city of Pittsburgh, from 1896 to 1906, before

joining McClure's magazine in New York. The

vital arts culture that flowered alongside capitalism in American

cities, especially Pittsburgh, New York, and Chicago, is one of

Cather's concerns in ¡��Paul's Case¡¨ and The Song of the

Lark. Cather made a home in New York for the rest of her

life. While she enjoyed the benefits of America 's cultural metropolis,

she also used it as a base from which to explore places that meant more

to her. Cather had first visited Europe in 1902, and she returned there

repeatedly, with an increasing focus on France in the 1930s.

|

|

|

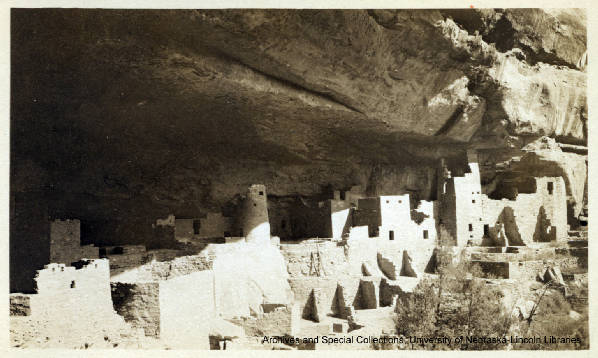

Mesa Verde, Colorado, around

1915.

Source: http://libtextcenter.unl.edu/cather/gallery/index.html

|

|

| |

She first visited the American Southwest ( Colorado, Utah, New Mexico,

and Arizona ) in 1912, and immediately recognized there an historical

depth she found lacking in much of North America. Here European

colonial and missionary contacts dated back to the 1500s, and the

Anasazi Indians had built fine stone cities into cliff walls in

pre-Colombian times. In The Song of the Lark and

The Professors House, Cather's characters

seek imaginative connections with these ancient Indians and with the

Europeans who first explored the region. Death Comes for the

Archbishop, focusing on two French Catholic missionaries in

New Mexico, recreates the mesh of French, Spanish, Mexican, Indian, and

Anglo cultures in the Southwest during the second half of the

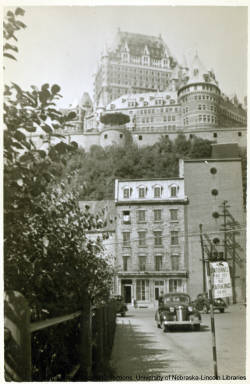

nineteenth century. In 1928 Cather visited Quebec City ( Canada ),

which inspired her next novel, Shadows on the Rock,

set in Quebec in the 1600s.

|

|

|

Chateau Frontenac, Quebec

City, 1928.

Source: http://libtextcenter.unl.edu/cather/gallery/index.html

|

|

| |

New Mexico and Quebec had a similar appeal for Cather: they were

predominantly Catholic cultures with rich histories dating back

hundreds of years. She found in them an alternative to American Puritan

history, centered in New England and originating in England. Her

alternative American history originated in France and Spain, and was

ultimately oriented toward Rome. By opening up this history Cather

brought cultural and geographical complexity to the American novel. She

demonstrated the continuity of the United States with the historically

Indian and French territory to the Northeast and historically Indian

and Spanish territory to the Southwest.

Cather's final work adds to the geographical complexity

of her accomplishment. Her last completed novel, Sapphira

and the Slave Girl, is set in antebellum Virginia, some

decades before she was born in that state. At the time of her death in

1947 she was working on another historical narrative, Hard

Punishments, set in 1340 in Avignon, France.

Top

|

|

|

|

|