|

|

|

|

| John Donne |

| �����D�� |

| �Ϥ��ӷ��G |

| �D�n�����GPoem |

| ��ƴ��Ѫ̡GFr.Pierre E.Demers/�ͼw�q����;Cecilia Liu/�B����;Kate Liu/�B����;Raphael Schulte/���ùp |

| ����r���GIntroduction to Literature 1998/1999/2000

English Literature

17th Century Restoration Period |

|

|

|

|

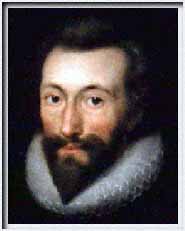

John

Donne

1572-1631

|

| �@ |

|

Early

Life A.

Studying

Law in Lincoln's Inn Early

Life A.

Studying

Law in Lincoln's Inn

B.

Marriage

Productive

Years

A.

Works Productive

Years

A.

Works

B.

Years

Abroad

Devotions to

Church Devotions to

Church

Remarkable Life

A.

Features

of Works Remarkable Life

A.

Features

of Works

B.

Last

Years

Metaphysical Poetry Metaphysical Poetry

Subject Matter Subject Matter

Language Language

Rhythm Rhythm

Religion Religion

|

| �@ |

Early

Life Early

Life |

| �@ |

Born in 1572, John Donne's father died when he was

merely 4 years old.

His mother Elizabeth

Heywood Donne, was the daughter of John Heywood, an interludes author

and a epigrammatist, and the great niece of Sir Thomas More. After Donne's father died, with three children, she

married six months later to John Syminges, an Oxford physician who

practiced his profession in London. Receiving

good education, Donne was tutored at home till 12, and then in 1584,

Donne entered Hart Hall, Oxford, where he spent 3 years, learning

French and Latin.

Donne probably attended

Oxford for three years and further to Cambridge, but he may also have

joined his uncle Jasper Heywood, who was charged of an underground

Jesuit mission in England and exiled, to Paris and Antwerp.

A.

Studying

Law in Lincoln's Inn

After spending one year at Thavies Inn, Donne

received further education as a nominated law student in Lincoln's Inn

in1592.

He stayed there and

studied law for two or more years. Then

perhaps Donne went on an adventurous trip. Soon on his return from the expedition to Cadiz and

the Azores from 1596 to 1597, Donne served as the secretary of Sir

Thomas Egerton, and hence developed high interest in foreign affairs

and state events.

Meanwhile, he

dissociated himself from Roman Catholicism.

B.

Marriage

In 1601, Sir Thomas Egerton's brother-in-law, Sir

George More brought his seventeen-year-old daughter Ann More with him

to London.

It was then Donne fell

in love with Ann More and married her in December the same year. The wedding was arranged and witnessed by several

of Donne's friends, and as Donne revealed the news to the bride's

father, Sir George More outrageously had Donne and his friends

imprisoned and demanded Sir Thomas Egerton to dismiss his secretary. The marriage turned out upheld and Donne reconciled

with his father-in-law. Despite

his happy marriage and increasing family, for the following twelve

years, he remained jobless on and off and depended much upon loans and

helps from relatives and patrons.

�@

TOP

|

Productive

Years Productive

Years

�@

|

| �@ |

A.

Works

It was this frustrating decade without regular work

that brought out Donne's productive and consecutive works. Most of his verse letters, sonnets, poems and

epithalamiums such as Biathanatos, Pseudo-Martyr, and Ignatius

his Conclare, were

written against Roman Catholicism. Donne's

famous secular poems, sonnets, and the famous Anniversaries for Elizabeth Drury brought him Sir Robert Drury's

attention.

B.

Years

Abroad

In 1611, Donne was invited and joined Sir Robert

Drury to the continental trip. It

was then Donne composed several of his most prominent poems, including

the famous ��A

Valediction: Forbidden Mourning��

for his wife to express his sorrow in leaving her and his children.

TOP

|

Devotions

to Church Devotions

to Church

�@

|

| �@ |

Though Thomas

Morton had long tried to persuade Donne to accept holy orders since

1606, Donne hesitated. It

was not until 1615 that he was ordained as a priest and accepted King

James appointment for a ministry. The

same year, Donne received an honorary doctoral degree of divinity

dedicated to him from Cambridge. But

two years later, John Donne was severely buffeted by the death of his

wife.

Ann More Donne deceased

because of childbirth. Within

their 16-year marriage, she gave him twelve children, only that five of

them died.

Ann's death left Donne

desolate and thence devoted himself to his work. In 1619, Donne served as an embassy chaplain in

Germany, and later he was appointed as the dean of St. Paul's Cathedral

in 1621.

TOP

|

Remarkable

Life Remarkable

Life

�@

|

| �@ |

A.

Features

of Works

Donne's works were famous for the themes of his

faith in God and women. Donne's

witty ability of depicting his belief of God, and fragile life of human

being and especially of women, though not writing with conventional

glamorous style of verse like the Petrachan style, Donne successfully

and beautifully connect the time and space in his poems with

extraordinary images. Donne's

usage of diction and language in composing his works is considered

revolutionary of his time. And

it is quite recently in the modern study of poems that his style is

regarded as ��metaphysical��.

B.

Last

Years

Donne reversed to work on prose more than ever in

his later years.

Most of his

distinguished prose, sermons and devotions were announced in his last

years.

In 1623, with his

writing of Devotions, Donne proved that his imagination was not at all

blunt because of his serious illness. Donne's last public sermon was Death's Duel in 1631. He

passed away one month after his sermon at court, but left the

contemporary with profound depictions of spiritual issues of divinity

with natural devices of language.

TOP

|

|

Metaphysical

Poetry Metaphysical

Poetry

|

| �@ |

The word��metaphysical��applied

to Donne and his followers refers to their conception of a unified

universe where all things physical and spiritual are related. All

things have a similarity between them, the most concrete object being

in some way an image of the most spiritual. For instance, in the poems

presented in this Study Guide,

the flea that has sucked both lovers' blood is the temple of their

union; the compass of Valediction

is an image of the high degree of love between a man and his wife; God

in Holy Sonnet XIV

is compared to a blacksmith. The prose also uses metaphysical imagery�wthe unity of

mankind is like a continent (Meditation XVII).

This

use of imagery requires wit; that is, the mental ability to join ideas

and objects apparently dissimilar and unrelated. The findings of wit,

the disclosure of similarity in the dissimilar, is called metaphysical

conceit, which is really the distinctive feature of metaphysical poetry.

Metaphysical

poetry is then characterized by the predominance of the intellect. Yet

what the intellect seeks to express is passion, feelings and emotions.

For instance, in the famous compass image of Valediction

the mind is very much at work, but it is at work on an analogy to a

deep feeling. The mind of the metaphysical poets is not trying to build

an intellectual view of a unified universe; it uses the unity of all

things to express their passions and their emotions. The metaphysical

poets are lyrical poets in whom thought and feeling are associated.

TOP

|

|

Subject

Matter Subject

Matter

|

| �@ |

The

main preoccupations of the metaphysical poets are love, death, and

religion. Most of the famous metaphysical poets were religious poets

having in mind the universe unified in God. But even the secular poems

offered here contain some religious allusions. In The

Flea, the black insect is a temple and a

cloister; The Canonization

is a mock elevation of the lovers to the state of the blessed in the

heaven of the god of love; A Valediction

forbids the listener to tell lay men the couple's love. Death also

pervades the secular poems�wthe

Killing of the insect in The Flea;

the act of love as being a dying in The

Canonization; the separation of the couple

compared to a peaceful death in A Valediction.

The religious poems and prose are immediately concerned with death.

Love, of God as well a of man, pervades all the works.

Yet

if we look a little deeper into the meaning of the poems, we realize

that (the main preoccupation of the metaphysical poets is themselves;

their own complex self-consciousness is the real subject matter.) In

his love poetry, Donne is not so much occupied with the description of

the charms of the loved one. We hardly find a feature of the girl

mentioned. What comes out with great reality is Donne's analysis of

himself in love. In the sonnets we find a complex expression of Donne's

feelings towards God and eternal life.

TOP

|

|

Language Language

|

| �@ |

Donne used images

taken from everyday life and from the sciences, technology and crafts

of his time. The language was also the language of everyday life, and

in this his poetry strikingly contrasts with the elevated style of

poets of his time, especially Spencer and Shakespeare. The

Canonization begins with:��For

God's sake hold your tongue and let me love,��which

is hardly poetic. (The language is the language of ordinary

conversation;) the structure of Donne's poetry is that of a dialogue of

which only one half is heard, a device called��dramatic

monologue��mage

famous by Browning in the XIX century.

TOP

|

|

Rhythm Rhythm

|

| �@ |

Donne's

deliberate use of conversational style creates a peculiar rhythmic

effect. The verse line contains a double series of stresses, one made

of the normal stresses of conversation, the other, of the staple iambic

foot of the verse. For instance, in the second stanza of The

Flea, the iambic feet require the following

scanning:

Oh

stay, three lives in one flea spare,

Where

we almost, yea more than married, are.

Yet

the conversation stresses required by the meaning are placed on quite

different syllables. The placing of the stresses depends a great deal

on the reader; the following is only one suggestion:

Oh

stay, three lives in one flea spare,

Where

we almost, yea more than married , are.

The

iambic stresses do not disappear under the impact of the stresses of

normal speech; they are only subdued and they combine with the

conversation stresses to from a counterpoint.

The

colloquial language also affects the verse line which often breaks open

at the end and runs on to the next line:

Soldiers

find wars, and Lawyers find out still

Litigious

men, which quarrels move, ...

The

King's real, or his stamped face

Contemplate...

Such

run-on lines abound in Holy Sonnet VII

and Holy Sonnet XIV:

At

the round earth's imagined corners, blow

Your

trumpets...

Batter

my heart, three-person'd God, for you

As

yet but knock...

The

counterpoint effect of the conversational style overriding the iambic

rhythm is echoed in the use of rime, Often the riming sound expected by

the listener, is slurred over by the speaker in the poem:

Soldiers

find wars, and Lawyers find out still

Litigious

men...

Where

the rime scheme requires a stronger word than��still.��The

strong stress falls on the run-on word��litigious��at

the beginning of the next line.

Rime,

language, and imagery all combine to give Donne and his followers a

poetic style that puts them apart from the main current of English

poetry from the Renaissance to the beginning of the XX century.

TOP

|

|

Religion Religion

|

| �@ |

Another

side of Donne's writing which requires special attention is his use of

religion. Many of the titles of his works show his love for religious

topics, even though he may be also writing sensual verses. This strikes

many readers as most strange. But the paradoxes which characterize his

poetry are matched by the seeming contradiction of his life; that is,

Jack Donne, the notorious young playboy, and Dr. John Donne, the

religious church minister.

The

poets of this century have learned from Donne's poetic method, by which

emotions are expressed by ideas and ideas defined in their emotional

contest. What interested Donne was not the ultimate truth of an idea

but the fascination of ideas themselves. He was not committed to a

particular philosophic system, but he was interested in conflicting,

fascinating, and often disturbing philosophies of his period. His

images are drawn from whatever beliefs or ideas best expressed the

emotion he had to communicate; that is, to describe an emotional state

by its intellectual equivalent.

When

T. S. Eliot praises Donne for keeping the proper union of intellectual

and imaginative sensibilities, it is perhaps related to the largely

��incarnational�� part

of Donne's life and work. Originally, ��incarnational�� meant the striking and paradoxical union of the

divine with the human after the model of the god-man Jesus Christ, When

applying the term to Donne's poetry, it means his attempt to combine,

balance, and reconcile opposites; for instance, the union of man with

the divinity, of heart with head, of female with male. It is curious

that so many of Donne's works try to describe the mystery of divine

love by shocking (though not necessarily irreverent) references to

human love and vice-versa. For example,

Except

You enthrall me, never shall be free,

Nor

ever chaste, except You ravish me. (Holy

Sonnet XIV)

In

another poem, he tries to raise ordinary secular love to the level, of

sacred love.

And

by these hymns, all shall approve

Us

canonized for love; (The Canonization)

Donne

is a typical writer of the��womb

to tomb��kind

of poetry. These poems are very frequently found in the larger contest

of love and religion; they are well illustrated by his double meaning

of die, for instance, signifying both death and sexual intercourse:

We're

tapers too, and at our own cost die,...

We

die and rise the same, and prove

Mysterious

by this love,

We

can die by it, if not live by love, (The

Canonization)

This

death-in-life-and-love type of poetry is touchingly described in, A

Valediction: Forbidding

Mourning a farewell poem addressed to his

wife on the occasion of his trip to the Continent; his wife had given

birth to a stillborn child during his absence.

Themes

connected with religion are frequently found in Donne's writings: for

instance, his concern with death (Meditation

XVII�e��No

man is an island...Three-fore thee.���f);

his fear of divine punishment because of sin. (Sermon

LXXVI�e��On

Falling Out of God's Hand���f;

and his painful resignation to God's will (Holy

Sonnet VII) .

A

saving quality of Donne's otherwise serious writing is his peculiar

sense of humor, which requires of the reader a certain tolerance for

the strange and the macabre.

Oh

stay, three lives in one flea spare,

Where

we almost, yea more than married, are.

(The

Flea)

A

bracelet of bright hair about the bone (The

Relic)

Neither

Donne's life nor works could be described as conventional. His witty

conceits are brilliant sparks of inspiration, a kind of inspiration

which the Greeks, at one time, attributed to the divinity. They are

divine in the sense that his poetic vision goes far beyond our ordinary

human condition and surprises us with its fresh originality as if it

had come from another land. But at the same time, his works are rooted

in that same human condition which makes him a kindred spirit with us.

. . a spirit incarnated.

TOP

|

| �@ |

�@ |

|

|

|

|