|

|

|

|

Twelfth Night: Or What You Will

|

| 電影導演 / Trevor Nunn |

|

|

Nunn's Twelfth Night

|

Margarette Connor |

Not all light and fun│One harsh review│A personal view│Trevor Nunn│Shakespearean "sound"

Camera work in Shakespeare│Not a "director's cut"│Cuts to the text│Fictional Illyria

Woman to man│Settings│Excellent public relations materials│Study Guide│Sources

|

| |

|

| |

Not all light and fun Not all light and fun |

| |

| |

|

| Imogen Stubbs as Viola, Helena Bonham-Carter as Oliva and Toby Stephens as Orsino. |

Twelfth Night is one of Shakespeare's fun plays, with its gender switching plot and tale of mixed identities. This film is a serviceable treatment of it, and it's enjoyable to watch. But perhaps it can seem a bit dated. As film critic Brian D. Johnson notes, "Now that gender-bending has become such a sophisticated conceit in film-making-with such landmarks as Orlando, The Crying Game and M. Butterfly-Twelfth Night's fake-moustache masquerade appears awfully tame."

And for a comedy it's not all lightness and fun, either. The darkness of the play is allowed to come through. "The darkness of the play is palpable on screen. It is there not just in the gloomy autumnal landscape of the film's world but also in the oppressive interiors of the buildings. … It is also there in the militarism of Orsino's kingdom, where soldiers chase Antonio when he is recognized, and where the shipwrecked Viola and sailors scurry for cover when a troop of Orsino's horsemen investigate the debris of the wreck on the seashore. There is, in this continual reminder of the war where Orsino's "young nephew Titus lost his leg" (5.1.59), a threat of mortality in which "youth's a stuff will not endure" because of death in war as well as the risk of growing up." (Holland) |

|

One harsh review One harsh review |

| |

| |

Most critics had nothing terrible bad to say about the film. It was seen as a pleasant entertainment, but Stanley Kauffman of The New Republic, disliked it terribly, and had this to say:

"The cutting and the rearrangements of the text are not much more severe than one is braced for, but he [Nunn] misconstrues the play's temper jarringly. Visually the film is seen mostly in a dreary gray climate--this play that seems entirely scented with flowers. Nunn cast Sir Toby Belch with a grossly unfunny actor, Mel Smith, who suggests nothing of the minor Falstaff in his part. … Maria, the maid who is a sort of cousin of Doll Tearsheet, is done by Imelda Staunton without an iota of merriment.

|

| Richard E. Grant as Sir Andrew Augecheek |

"Imogen Stubbs, as Viola, one of the most romantic roles ever written, has all the warmth and color of a popsicle. Orsino, the count whom she/he serves, is played in a muffled manner by Toby Stephens, with no poetic line. A few people in the cast suggest what they might have done with their roles in a full-bodied production. Helena Bonham Carter, as the Countess Olivia, who falls in love with the disguised Viola, moves feelingly from mourning for her dead brother to longing for the youth. Nigel Hawthorne is a perfect Malvolio, Olivia's steward, or would be if he had not been urged by Nunn to distend his pomposities. And Ben Kingsley makes Olivia's jester, Feste, a shrewd philosopher with dignity under the motley." |

|

A personal view A personal view |

| |

| |

I usually quite enjoy Kauffman's reviews, but I thought he was way off the mark for this one. Mel Smith is never a "grossly unfunny actor," and indeed, in England, he is known as a comedian. I quite enjoyed Stubbs and Stephens, as well, so there's no accounting for taste. Perhaps the harsh review is because Kauffman is American, and the film is particularly British--its director, cast and setting are all English, as is the production company, and, of course, the playwright. British and American films have quite different aesthetics.

|

| Mel Smith as Sir Toby Belch |

Stubbs had something interesting to say along this line: "It's a welcome break from the American kind of film realism. When acting onscreen, you're often asked not to act; you're exploited for some quality the director sees in you. But in Shakespeare, you are forced to act--to tell the audience, 'This is a character. This is a play.'" (Corliss) |

|

Trevor Nunn Trevor Nunn |

| |

| |

|

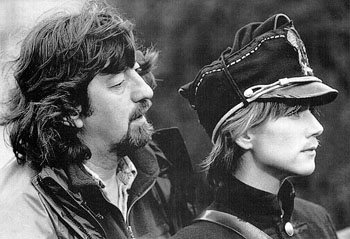

| Director Trevor Nunn with his leading lady and wife, Imogen Stubbs in costume as a young man. |

Trevor Nunn is one of the world's foremost Shakespeare directors. For eighteen years he was the artistic director of the Royal Shakespeare Company. For his screen version of Twelfth Night, he pulled together a cast of some of England's finest classical actors and comic talents including Helena Bonham Carter, Nigel Hawthorne, Ben Kingsley, Richard E. Grant, Mel Smith, Imogen Stubbs, who, incidentally, is Nunn's wife, Imelda Staunton, and Toby Stephens, son of the late Sir Robert Stephens and Maggie Smith. |

|

Shakespearean "sound" Shakespearean "sound" |

| |

| |

I thought most of these actors sounded great. The Shakespearean language sounded fresh and alive, and the poetry came through. Nunn had this to say about working with the poetry in Shakespeare and helping actors "sound right":

|

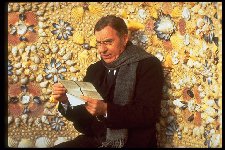

| Nigel Hawthorne as Malvolio |

"I was very fortunate because I had ten days to rehearse with the actors before we started shooting. Most of the actors … were immensely experienced in classical work, particularly in Shakespeare. Mel Smith, a renowned English comedian, was inexperienced in Shakespeare, but he was very responsive, very interested in direction, and in analyzing the text, and in any hints I could give him about how best it should be spoken. Helena [Bonham Carter] had not done a Shakespeare play before, but she and I had worked together before on Lady Jane, which had to do with renaissance society, and we'd read a number of texts together on that occasion, so I felt she was fairly well qualified. … So I think there can be any number of cases where actors, like Helena or Mel, haven't any Shakespeare experience, but they were prepared to do the work and they were working with someone sufficiently knowledgeable or experienced to be able to provide the background and to help them. I don't think an ad hoc approach to Shakespeare is in any way defensible. … There are God knows how many theories [about how to recite Shakespeare], some of them sensible, some of them completely daft, but you're bound to get people with all of those different ideas gathered together in a room. So not only does clear arbitration have to happen, and in many cases clear instruction, but textual analysis has to be done in considerable detail, or it just isn't going to be possible for actors under the prevailing conditions of film production--you know, you're in the trailer, doing make-up, or waiting for the weather, and suddenly you're on, and you have to deliver. If you're not prepared, you're not going to have any opportunity on the set to have insights into alternative meanings, to begin to adjust inflection, to discover that rhythmically you're all wrong, that the important thing is that the line is an irregular line and not a regular line, because that's the effect that Shakespeare is after. You can't do that on set." ( Cineaste ) |

|

Camera work in Shakespeare Camera work in Shakespeare |

| |

| |

|

| Lady Olivia in mourning, but ready to be happy again. |

Along the same lines, he later said, "It seems to me that the camera requires work of actors that is quite fundamentally untheatrical and unstylized. It requires actors to be as truthful as is conceivably possible. The camera is associated with eavesdropping on the real event. Consequently, what is said in front of the camera needs to convey to the cinema audience the sense that it has not been written, that the language of the screen is being invented by the character in the situation spontaneously at that moment. We must not be aware of the writer. The challenge that I gave to the actors was that every syllable of that text had to be in order, as written, every pentameter, and in some cases half-line pentameters, had to be accurately learned and observed, but it was essential that I should remain unaware of a writer. I wanted that sense that it was being spoken in real situations and being invented by the characters.

"That's more possible with Twelfth Night than in many texts, because a lot of the play is in prose and therefore the imperative for the rhythmic line is less obvious. The play breaks into verse at key moments of high romance, of deep feeling, but a lot of it was written at a time when Shakespeare himself was exploring the possibilities of real speech, overheard speech, and slang. In addition to retaining as much of the text as possible, my aim was to keep it very tightly on the leash as far as its accuracy is concerned, and yet encouraging every conceivable foible of naturalistic delivery was the task that I set the actors. Indeed, I said to them, if at any point I feel you are reciting something by a great writer, then it's going to be cut, start again." ("Shakespeare in Cinema")

For Nunn, the challenge was to make his audience see the psychological coherence of the play. "I've actually set out four or five times to direct the play and so I had thought about it a great deal before embarking on the film version," he said. "I felt the urge to make the content of the play seem real, and not pantomimic or stylized, so that the contrary extremes of sexual behavior in the central characters are seen in a believable social context. The story sets out to provoke both genders in the audience, so it's important that spectators shouldn't be able to get off the hook of the play by dismissing it as an improbable, archaic comedy." (Fineline) |

|

Not a "director's cut" Not a "director's cut" |

| |

| |

Peter Holland, Director of the Shakespeare Institute, Stratford-upon-Avon, England, had this to say about the film: "Surprisingly, Nunn has never directed Twelfth Night in the theatre. His fascinating introduction to the published screenplay for the film is a story of disappointments: of stage productions that never quite happened and of the endless compromises that making the film necessitated. That introduction explains much, not least why the pre-credit sequence showing the shipwreck that divides Viola from Sebastian is accompanied by a curious commentary in fake Shakespearean verse; like the problems with the movie Blade Runner, the studio's money-men decided, after a test screening in Orange County, that audiences could not be expected to follow the plot and needed a voiceover to tell us what we were watching. Like Blade Runner, one day we may get the "director's cut," the version Nunn would have liked us to see." |

|

Cuts to the text Cuts to the text |

| |

|

As usual, in the film version, there must be cuts and changes to the original text, and this is what Nunn had to say about them:

"In my view, Twelfth Night is as near a perfect work for the theater as any that one can nominate. It's exquisite, as perfect as The Marriage of Figaro is in opera, or as perfect as Some Like It Hot is as a movie. It is that fine and balanced, it has perfect

|

| Olivia has emerged from mourning and is ready for love. |

equipoise. So one tampers with it at one's peril. I did several things I'm sure would mortify some scholars. I introduced a prologue, because it was discovered that audiences were having difficulty in orientating themselves, and trying to discover exactly who these twins were. I thought it was a good idea to provide an extra sense that Feste is an observer and to some extent a teller of tales, especially because of the content of his final song, and so I liked the idea of Feste having some introductory

material that gave us a context. I tried to make that before the credits, so that as it were William Shakespeare's play started after the credits. I also did a certain amount of transposition, partly because I wanted to clarify narrative, and, in one all-important area, to emphasize ironic counterpoint. I fought to keep as much of the text as possible, and I lost some of the battles, but we retained about sixty-five percent of Shakespeare's text and I think that compares favorably with a lot of recent Shakespeare films where one is down to forty or even thirty percent of the original text. That strikes me as almost a contradiction in terms, that you're doing a great work by Shakespeare, but you're not prepared to include his language." ( Cineaste) |

|

Fictional Illyria Fictional Illyria |

| |

| |

He sees the play's locale, Illyria, as "indeed a fictional country; but even so - not that fictional," peopled as it is with Italianate sounding lovers side by side with Sir Toby Belch and Sir Andrew Aguecheek whose names lead us to expect a very English class hierarchy. Nunn and the film's designer, Sophie Becher, worked to create an Illyria that is both rational and poetic - creating a version of the 1890's, an age close to the social and historic grasp of today's audience but also a time when Viola's efforts to become a boy would have to be particularly extensive. (Fineline) |

|

Woman to man Woman to man |

| |

| |

"It was important to me that Viola, converting herself into her brother, Sebastian (who she believes has drowned) should have to face considerable physical and temperamental challenges," says Nunn. "So I wanted the film to be set at a time when, in their silhouette, men were clearly men - no frills and lace - and when conversely women were expected to be very cosmetic, frail and delicate creatures, to be protected from the harsher realities." (Fineline)

Orsino's household is portrayed as an all male military court, such as many middle-European principalities once boasted, so (as Cesario) Viola has to learn how to fence, ride at the gallop, smoke, drink and play billiards. "When I'm being a boy," says Imogen Stubbs, "I have to remember that I'm playing a girl - who is not an actress - playing a boy. On the whole, Trevor has Viola being quite good at being a boy, finding it both frightening and immensely liberating." (Fineline) |

|

Settings Settings |

| |

| |

When speaking about his choices on setting in Cineaste, Nunn had this to say:

"It was wonderful to be able to have Olivia's household as a place where you could imagine how strong that father's influence had been, how stricken the household was with the unexpected death of the brother, and how it had lurched towards stasis, that it could almost not run as a household because of Olivia's grief and waywardness, and therefore the house had become dependent on Malvolio. The scale of the house, the number of servants, and the workforce needed to keep the place running, somehow gave extraordinary authority and credibility to Malvolio. So there's a whole set of circumstances which can be presented only because of cinematic verisimilitude that provide layers of, first of all, credibility and, finally, of tragic meaning to Malvolio's story.

|

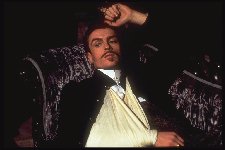

| A wounded Orsino recovers at home |

"I also liked the challenge of saying, `If Viola is going to present herself as a boy in Orsino's court, what sort of court is it?' I reached the conclusion that there were no women there, it was like a military academy, that again it was a place where his father had had a very strong influence and this young nobleman was also slightly out of control, that the military authority for the area had no strong leadership anymore. I liked the idea of Viola having to pass a whole number of tests before anybody was going to really buy the story. I enjoyed the challenge of saying we've got to believe in Orsino's belief in the boy, because then a real miracle can happen at the end, because the work is so overwhelmingly about gender. Shakespeare constructs the story so that, for very believable reasons, Viola has to become her brother. It's a way of keeping him alive, even though she's accepted the fact that he's dead, because by becoming him she can stop hating herself for being the one who was saved, and she can somehow imagine that she's keeping him alive in this world, and trying to behave as he would behave. All of that becomes very credible when you turn the requirements of cinematic naturalism on it." |

|

Excellent public relations materials Excellent public relations materials |

| |

| |

Fine Line Features, the distributor of the film, provides excellent public relations materials for the play, and I'd like to share some of the comments in them here. Each actor was asked to give insight into his or her character.

The fourth young lover is Orsino (Toby Stephens), just returned from battle and, in this version, recovering from a wound. "He hardly knows what's happening to him," says Stephens. "He's a young shell-shocked soldier obsessive about Olivia. He's the Duke of Illyria, with a military academy to run, but he's not running it very well because he can think of nothing except Olivia. But, gradually, a real love story takes over from the fanciful romantic one. The resolution is all about real love." (Fineline)

Feste is an observer. He sees through people. Though he's a kind of entertainer, who will only perform for money, what he chooses to sing to people is intentionally relevant and disturbing to them." "People find the truth very hard to deal with," notes Ben Kingsley. "This story shows people avoiding the truth at every level." (Fineline)

"A slightly disenfranchised human being," says Smith of his Belch. "To all intents and purposes a drunk, for two-thirds of the film at any rate. Clearly unfulfilled, unable fully to grow up and living on other people's money, principally Aguecheek's." (Fineline)

|

| Imelda Staunton as the fierce Maria. |

Malvolio's comeuppance is accomplished largely through the cruel ingenuity of Maria, who finally marries Sir Toby. "I played this part twice and hated it," says Imelda Staunton. "But what's so good about this adaptation is that she is not a pert and jolly maid but a woman of a certain age who is desperate to catch Sir Toby - it's her last chance. So she's prepared to be cruel to Malvolio (who's been cruel to her), to get what she wants."

Malvolio earns the hatred of Sir Toby for puritanically and hypocritically attempting to curb any fun or enjoyment in Olivia's household, provoking from Belch the challenge, "Dost thou think because thou art virtuous there shall be no more cakes and ale?" The plotters lead Malvolio to believe that the Lady Olivia has fallen for him and that he, a middle-aged servant, is destined to marry a beautiful young heiress. It is a savage joke: in this version, Malvolio's hopes and fantasies are hinted at very early on as Olivia leans on his arm at the funeral of her brother; at the end of the story, he blunders out, vowing to be "revenged on the whole pack of you."

"He's a sad man," says Hawthorne of Malvolio, "and in many ways completely ludicrous because he displays the height of conceit and pomposity. Observe my toupee (which took on a life of its own and became known as 'Colin') - when it goes on, and the frock-coat uniform goes on, you are looking at a man of great dignity. But when he plays out a seduction scene with the lady of the house, dressed in yellow stockings, and cross-gartered (as he has been duped into believing she prefers him), you see him making a complete fool of himself. He is then assumed to be mad and locked in the coal shed, where he is baited by Feste. It's a very funny part of course, but sad nevertheless. There can be no more toupee after the public ridicule he suffers. Good-bye Colin." |

|

Study Guide Study Guide |

| |

| |

Fine Line also offers a multi-media study guide that might be worth using with students. It can be found here:

http://www.finelinefeatures.com/twelfth/guide.htm

I have not used it with students, so I can't talk about experiences, but looking at it, it looks worthwhile for junior high school students and above. |

|

|

| |

Corliss, Richard. "Suddenly Shakespeare." Time, Nov 4, 1996 v148 n21 p88(3).

Fine Line Feature's Twelfth Night pages: http://www.finelinefeatures.com/twelfth/

Holland, Peter. "The Dark Pleasures of Trevor Nunn's Twelfth Night." Shakespeare Magazine: For Teachers and Enthusiasts. http://www.shakespearemag.com/spring97/12night.asp

Johnson, Brian D. "Twelfth Night Review," Maclean's, Nov 11, 1996 v109 n46 p74(2).

"Shakespeare In The Cinema: A Film Directors' Symposium." Cineaste, 12/15/98, Vol. 24 Issue 1, p48, 8p, 8bw |

|

All photos courtesy of Fine Line Features: http://www.finelinefeatures.com/twelfth/ All photos courtesy of Fine Line Features: http://www.finelinefeatures.com/twelfth/ |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

|

|

|

|

|